Yuelin Li

Year of birth: 2000.

Where do you live: New York.

Your education: Parsons School of Design MFA in Design and Technology, Tsinghua University BFA in Art and Technology.

Describe your art in three words: Sentimatter, Impermanence, Emotion.

Your discipline: Kinetic Sculpture, Installation, Agency of Materials.

Website | Instagram

Your works often balance between motion and stillness. How do you decide what kind of movement a piece should have?

I’ve always been drawn to objects in motion, but I’m even more captivated by the moment they pause to hold their breath and wait. Viewers often respond in a similar way. During the exhibition of I Know a Place, whenever the automaton came to a stop, the entire space would sometimes fall into stillness.

In my practice, movement feels closer to breathing, or to hesitation. I’ve come to believe that slowness holds more emotional weight than speed. A soft rotation or an uncertain shift aren’t just performing, but dwelling. Sudden pauses and irregular delays become part of the sculpture’s grammar, as if the piece were saying: “I’m not quite sure where to go.” This kind of paused motion, this quiet negotiation with time, reflects how we navigate relationships—tentatively, slowly, often unresolved.

This emergence is also shaped by the nature of materials. Some resist movement, while others are restless from the beginning. Motion arises through this ongoing dialogue, from listening to the inclinations and resistances embedded in each form.

You describe your sculptures as having “their own quiet agency.” Can you talk more about how you think objects express themselves?

Every object carries its own memory and tendency. Reclaimed metals, with their rusted edges and broken joints, don’t arrive as blank materials. They come with a quiet resistance and a sense of history, asking to be approached on their own terms.

Jean Bennett, in Vibrant Matter, describes materials as having vitality, or a capacity to act, resist, and express. I feel that in the studio. A piece of metal that won’t weld properly, or only fits in a certain way, isn’t just being difficult. It’s communicating. That resistance is part of its agency.

I don’t usually start with drawings. I place the materials on a large table and spend time with them, touching, shifting, waiting. As Tim Ingold also suggests, materiality isn’t fixed, but emerges through making. My role isn’t to shape it into something, but to listen. Most of the time, I feel more like a witness, holding space for the material to become what it already is.

Yuelin Li | See My Absence

Yuelin Li | See My Absence

What role does impermanence play in your creative process, especially when working with materials like ice or fragile mechanical systems?

Impermanence has always been embedded in my way of thinking through making. It stems from the physical nature of materials, but also shapes how I understand the unfolding of a work. I often respond to this sensibility through the work itself.

When I use ice, melting becomes a marker of time. In See My Absence, the ice face, made from a mold of my own face, gradually dissolves under observation. It doesn’t rely on metaphor. It meets the viewer through a direct, embodied disappearance.

Loose wires, fragile structures, and unexpected malfunctions form part of the work’s syntax. Over time, I’ve come to see fragility and impermanence as a language of emotion. It speaks of tenderness, uncertainty, and the inevitability of change.

For me now, making is a practice of both precision and release. I build with full intention, while also accepting that the work will eventually disappear. Its vanishing is part of how it becomes.

How do you want viewers to interact emotionally with your installations?

To be honest, I don’t think much about the viewer’s reaction while creating. My focus is simply to express myself with honesty. I don’t want to guide or instruct how someone should feel. What matters more to me is building an atmosphere where emotion can arise on its own, quietly and without pressure.

The movement of the piece, the click of metal, the hum of a motor, and the slow rhythm of the system all gradually draw attention inward. The experience becomes intimate, like the silence that happens when someone is truly listening.

Sometimes, viewers will stand in front of the work for minutes, watching a gear turn slowly, or witnessing an ice face melt, moment by moment. I’ve seen people respond with excitement, with tears, or with stillness. These moments feel deeply meaningful to me. Occasionally, in conversation afterward, viewers share stories or emotions that resonate with what they saw.

Many of your works seem to suggest solitude and introspection. Are these themes rooted in personal experience or broader observations?

In my work, solitude is not a theme I consciously select. It emerges as a condition that has always been present. Since childhood, I have been sensitive to presence and disappearance, and to the uncertainty that underlies all human connection. This world never allows two beings to move together indefinitely.

After I completed See My Absence, my mother reminded me of an animation I watched often as a child—The Snow Child. In the story, a rabbit builds a snowman who later sacrifices himself in a fire, evaporating into steam and drifting into the sky. I didn’t have the words for it back then, but I cried every time. That story stayed with me. Over time, it returned to me through the emotional texture of loss and the visual vocabulary that began to form in my work.

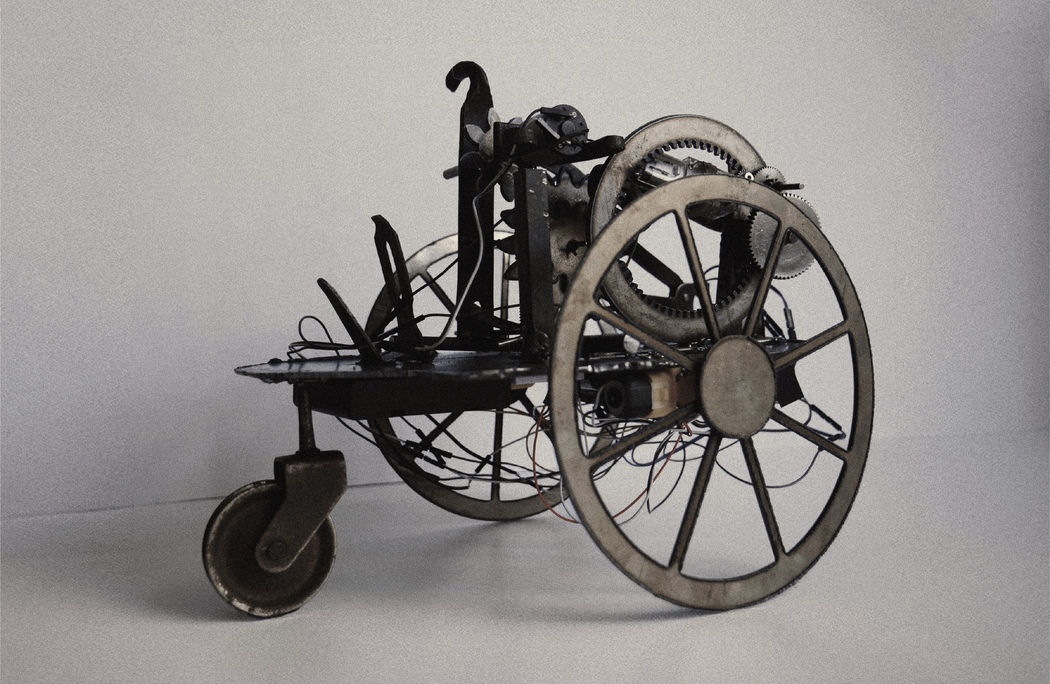

In I Know a Place, the automaton and helium balloon are connected by a single thread. They move together, but their relationship is fragile, always shifting between pull and lift, tension and imbalance. The automaton pulls forward with uncertain force, while the balloon floats up and down, carried by unstable air. Above them, a suspended field of threads, each tipped with a needle, defines a moving boundary they must navigate. The movement is slow and hesitant, shaped by constant adjustment.

I’m drawn to that suspended space, where friction between materials and quiet tension create a posture that hovers between closeness and separation.

What inspires your choice of materials—like rusted metal, gears, balloons, and translucent surfaces?

When I choose materials, I focus on how they behave and whether they can take part in the concept and rhythm I’m building. Qualities like responsiveness, weight, tension, or transparency often guide my decisions more directly.

Before making any choice, I often ask myself: which material can best articulate the concept of this piece? Then, through touch and working alongside the material, I make the next decision.

To me, rusted metal holds a sense of gravity and reveals the traces of time. Gears carry rhythm and direction. They help express slowness, friction, or misalignment. Balloons are sensitive and unpredictable—their instability works well for expressing suspended or uncertain presence. Translucent materials blur edges and create a space that feels fleeting or in-between.

I often visit scrapyards or recycling centers. I’m not looking for specific parts. I look for fragments that trigger a tactile or perceptual response. A curve, the tension of a surface, the way something receives light; qualities that can immediately connect to a gesture or emotional state I’m working with. Materials help shape the language it speaks.

How does your background in both art and technology influence the way you build your sculptures?

My background in technology gives me more freedom to imagine how a sculpture can be built and how it might behave over time. It opens up possibilities for movement, interaction, and timing. But I approach technology carefully. Any system I add, whether a sensor or a control mechanism, has to serve the emotional and conceptual structure of the work.

In See My Absence, I used a very simple hardware setup that allows the ice face to slowly turn toward the viewer. The motion is subtle, but it creates a sense of attention and quiet response, adding emotional weight to the piece. It wasn’t about showing off technical skill. It was about making a presence more perceptible.

I never use technology to make something look advanced. I care more about whether it allows the work to communicate something clearly, something that might otherwise remain invisible.

Leave a Reply