Audrey Ni Ruorong

Your work intertwines folklore, surrealism, and horror. What first drew you to these themes, and how do you see them resonating in contemporary visual culture?

My work has always been closely connected to my personal experiences. From a young age, I was fascinated by urban legends and horror stories, and later, a personal paranormal encounter became the catalyst for formally integrating horror or weirdness into my artistic practice.

As for folklore, it is simply a category for me, not as mysterious or niche as it might sound. Every culture has its own regional and historical characteristics. Anything circulating within a particular group or area can be called folklore, and its boundaries are inherently blurry. Categorizing things as folklore is not particularly meaningful to me. It’s more of an external labeling system.

Surrealism and postmodernism are closely tied to my current research. I’m developing my own Weird Methodology, and surrealism is a significant inspiration and practical tool in this process. Both visually and conceptually, surrealist techniques help me articulate many experiences that would otherwise remain ineffable. Postmodernism emphasizes both the ways in which language constructs reality and its incredulity toward metanarratives. Surrealism embodies these ideas perfectly, enabling me to explore the boundaries of reality through fragmentation and the questioning of perceived truths.

The reason these themes resonate in contemporary visual culture is straightforward for me: our curiosity about the unknown and the uncanny is rooted in human nature. For instance, everyone might have so-called “serious” books or encyclopedias at home, but when we’re kids, what we really love to read is pulp fiction. Today, how we receive information has changed significantly—urban legends have shifted from oral tradition to internet-generated content. Yet, the desire to explore the unknown remains the same; it’s just expressed differently through new media.

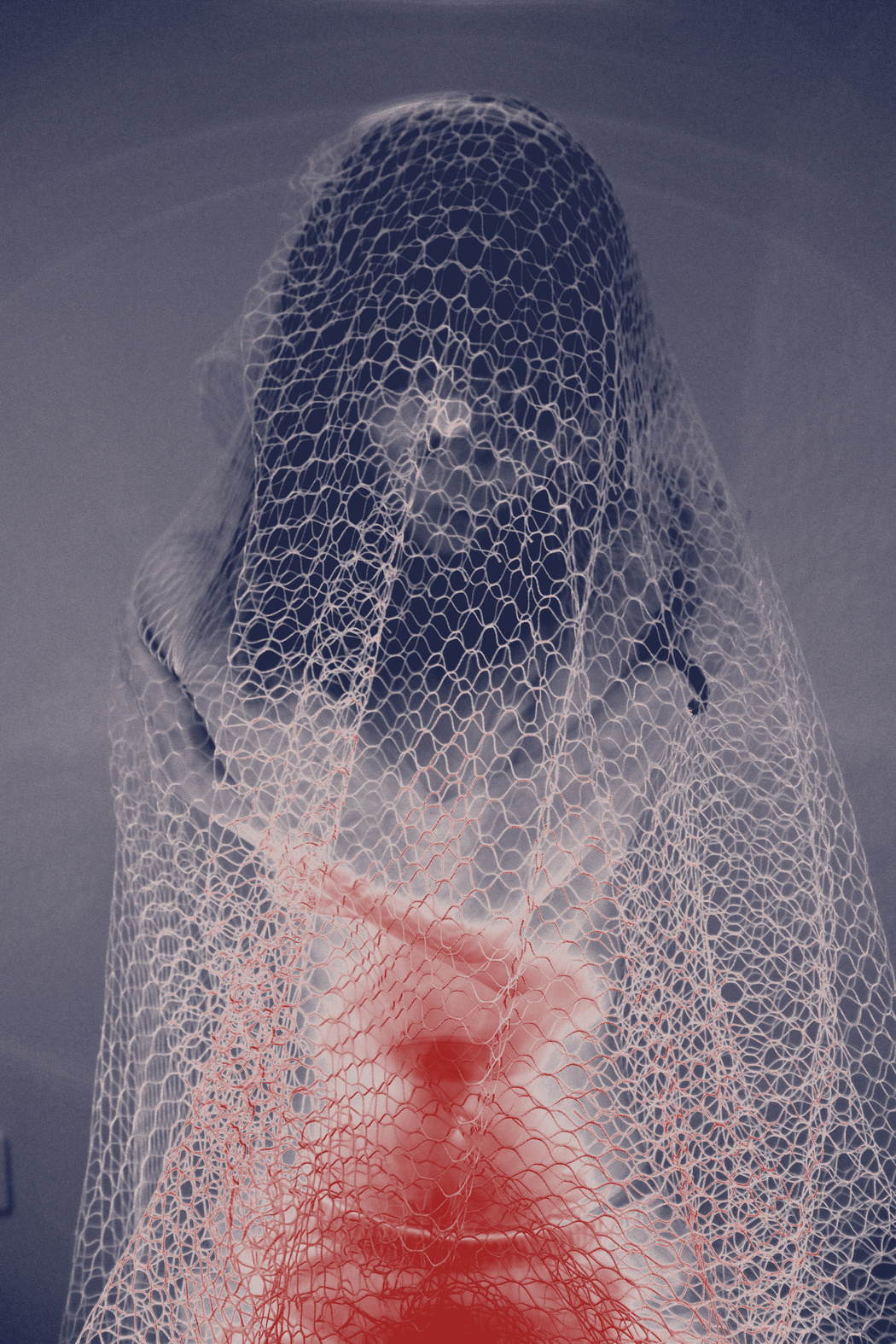

Audrey Ni Ruorong | Is It | 2024

Audrey Ni Ruorong | Is It | 2024

Your work is deeply influenced by “Weird Fiction,” particularly the New Weird movement. How do you translate the atmosphere of literary weirdness into visual media? And how does your understanding of New Weird—especially in contrast to traditional horror or fantasy—shape your artistic choices?

In my current practice, New Weird occupies a central place, though my formal focus on this direction began only in 2023. Strictly speaking, among the works I’m sharing here, very few explicitly deal with New Weird. Only one collage titled “Is It” touches upon this theme, and even that is just a fragment of an ongoing project. However, since New Weird is at the heart of my current research and creative practice, I’m glad to have the opportunity to discuss it.

New Weird is a contemporary evolution of Weird Fiction, which itself is a hybrid literary genre blending elements of horror, science fiction, and fantasy. The essence of this genre isn’t traditional fear but rather the creation of the incomprehensible. Weird Fiction, represented by authors like H.P. Lovecraft (representing Old Weird) and China Miéville (representing New Weird), features monsters and phenomena beyond human comprehension, entirely different from clearly defined figures such as werewolves or vampires in gothic or traditional horror stories. The creatures and events depicted in Weird Fiction surpass human experience, defying classification and human-centric understanding. An anti-anthropocentric perspective permeates the entire genre. Lovecraft’s protagonists often state their inability to describe or comprehend their experiences, resorting to chaotic, contradictory, and fragmented language. Readers experience the weirdness through the collapse of language and cognition itself.

The most significant difference between Old Weird and New Weird lies in characters’ attitudes toward the incomprehensible. Protagonists in Old Weird are typically nihilistic, prone to despair or retreat when faced with the inexplicable. In contrast, characters in New Weird proactively engage with the unknown, attempting to analyze and solve mysteries through various methods, whether scientific or occult like tarot reading. Seemingly contradictory systems coexist within the New Weird worldview. Rather than avoiding or despairing, these characters actively participate, seeking to understand and engage with incomprehensible phenomena on their own terms. This exploratory process is what draws me to New Weird. Moreover, while monsters in Old Weird draw on imagery from Western mythology, each New Weird author builds their own unique monsters and worldviews.

So, it’s clear that the main challenge of visualizing the Weird is that it is essentially “unvisualizable.” Literature can evoke incomprehensibility effectively through textual ambiguity and confusion, but visual representation risks unintentionally providing explanations, thus losing the intangible power of the unknown. Therefore, my approach is not about visually reconstructing specific monsters or scenes but rather dissecting and visualizing the structural process through which Weird fiction generates its unsettling atmosphere. What I visualize is not a single image but the process itself: my own confusion, attempts, and struggles as I confront the incomprehensible. Through this, I’ve gradually developed my own Weird Methodology, and related works are still in progress; stay tuned.

Audrey Ni Ruorong | The Final Straw | 2021

Audrey Ni Ruorong | The Final Straw | 2021

How does your background in comparative literature shape your visual storytelling?

It’s difficult to say that I have a background in comparative literature. My undergraduate studies were in computer science, so I never underwent formal comparative literature training. However, while researching New Weird fiction and writing literature reviews, I have drawn upon comparative literature methods.

So, comparative literature doesn’t directly shape my visual language. If there is an influence, it’s that my current practice approach feels like archaeological excavation, searching for connections and gaps among various narrative fragments and systems. Comparative literature helps me recognize hidden relationships among these fragments and makes it easier for me to capture cross-disciplinary and cross-media details in my visual expressions.

Can you walk us through your process of integrating digital collage, AI, and field-based narratives into a coherent visual piece?

The works I’m currently showing haven’t yet incorporated AI; AI is being used in a newer project still under development. Regarding integrating digital collage, AI, and field narratives into a coherent visual work, there’s an underlying question worth addressing: why emphasize coherence?

Our perception of the world isn’t inherently continuous—we constantly blink, creating fragmented perceptions. It’s our brains that stitch these fragments into a seemingly coherent whole. In my current practice, I’m more interested in what happens when I present a narrative that appears structured but is fundamentally fragmented. How would AI interpret these discontinuities? And how would the audience interpret them? That’s what intrigues me.

I never pursue absolute coherence, that’s not my goal. For instance, a jump scare works precisely because it’s abrupt, not coherent. For me, incoherence isn’t a problem; given that my current focus, New Weird, inherently involves incomprehensibility, something completely understandable and cohesive wouldn’t align with my objectives. Instead, I’m exploring how fragmentation, confusion, and discontinuity can generate novel viewing and interpretive experiences.

Audrey Ni Ruorong | Meng Po | 2022

Audrey Ni Ruorong | Meng Po | 2022

Much of your work explores ambiguity and temporal distortion. What does time mean to you in the context of storytelling?

Intellectually, I understand that time is an illusion. However, emotionally, I haven’t fully accepted this reality. Creating my work is, in a way, repeatedly confirming and attempting to convince myself to accept this fact.

Within storytelling, time serves as a technique or structural tool. Subjective linear time allows narrative manipulations such as flashbacks, flash-forwards, or temporal disruptions. These methods are more than mere narrative tricks—they effectively engage the audience’s perception. Time itself becomes material through which I deconstruct and reconstruct narratives, each exploration rearranging the logic of the world.

Your images often feel like fragmented memories or dreams. Do you deliberately work with subconscious or intuitive elements during creation?

Currently, I’m developing my Weird Methodology, with surrealist techniques playing a critical role. But even before explicitly structuring this methodology (prior to 2024), my works already demonstrated automatic or subconscious methods.

Looking back, my use of these techniques was conscious but driven by intuitive interest rather than systematic theoretical foundations. After 2024, when I began systematically reviewing my creative path, I realized I could formalize these intuitive methods into a coherent methodology. So, rather than starting to use subconscious and random elements suddenly, I’ve always employed them, initially because “it felt right,” and later because “I understand why I’m doing it.”

I’ve always been drawn to possibilities and enjoyed the unpredictability brought by randomness. Previously, I felt like someone drawn toward a fascinating constellation from afar. Now, having integrated these experiences into my methodology and worldview, I recognize that I’m not searching externally; instead, I’ve always existed within a system inherently filled with randomness and possibilities.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.