Sophie Jaffro

Where do you live: Vannes (Bretagne), France

Your education: Scientific Baccalauréat, École Supérieure d’Art d’Avignon (France): Bachelor summa cum laude and Masters

Describe your art in three words: Organic, abstract, detailed

Your discipline: Drawing, China Ink

Website | Instagram

Your work begins with observation sketches of natural forms. What draws you to these organic structures in the first place?

I have always been interested and inspired by organic forms. As a student, I chose to work for my degree and my thesis on the lines and the creation of shapes, both in art history and in nature. It led me to study, observe, and draw natural structures and shapes. I had to understand and spot natural expansion systems in growing and living things such as plants, lichens, mold, fungi, and mineral structures. Alongside my China ink work, I also work on an imaginary bestiary inspired by animal oddities. I rearrange and assemble elements observed on existing species and this project is fed by observation sketching. In all aspects of my work, I pay particular attention to our environment and the forms that compose it, which allows me to translate them through art.

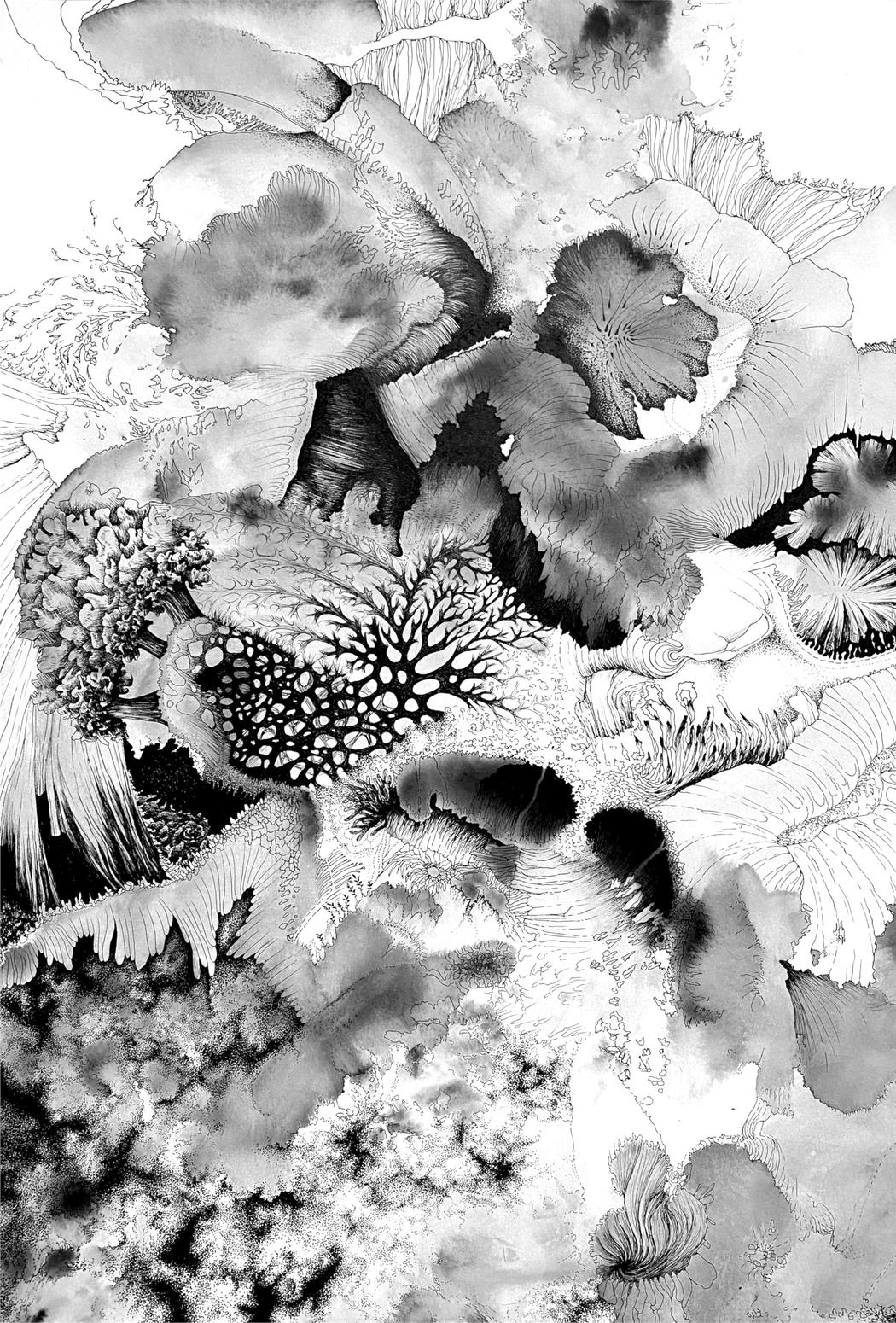

Sophie Jaffro | Immersion

Sophie Jaffro | Immersion

You often describe ink stains as a “seed” for the drawing. At what moment do you decide to intervene and start guiding the form?

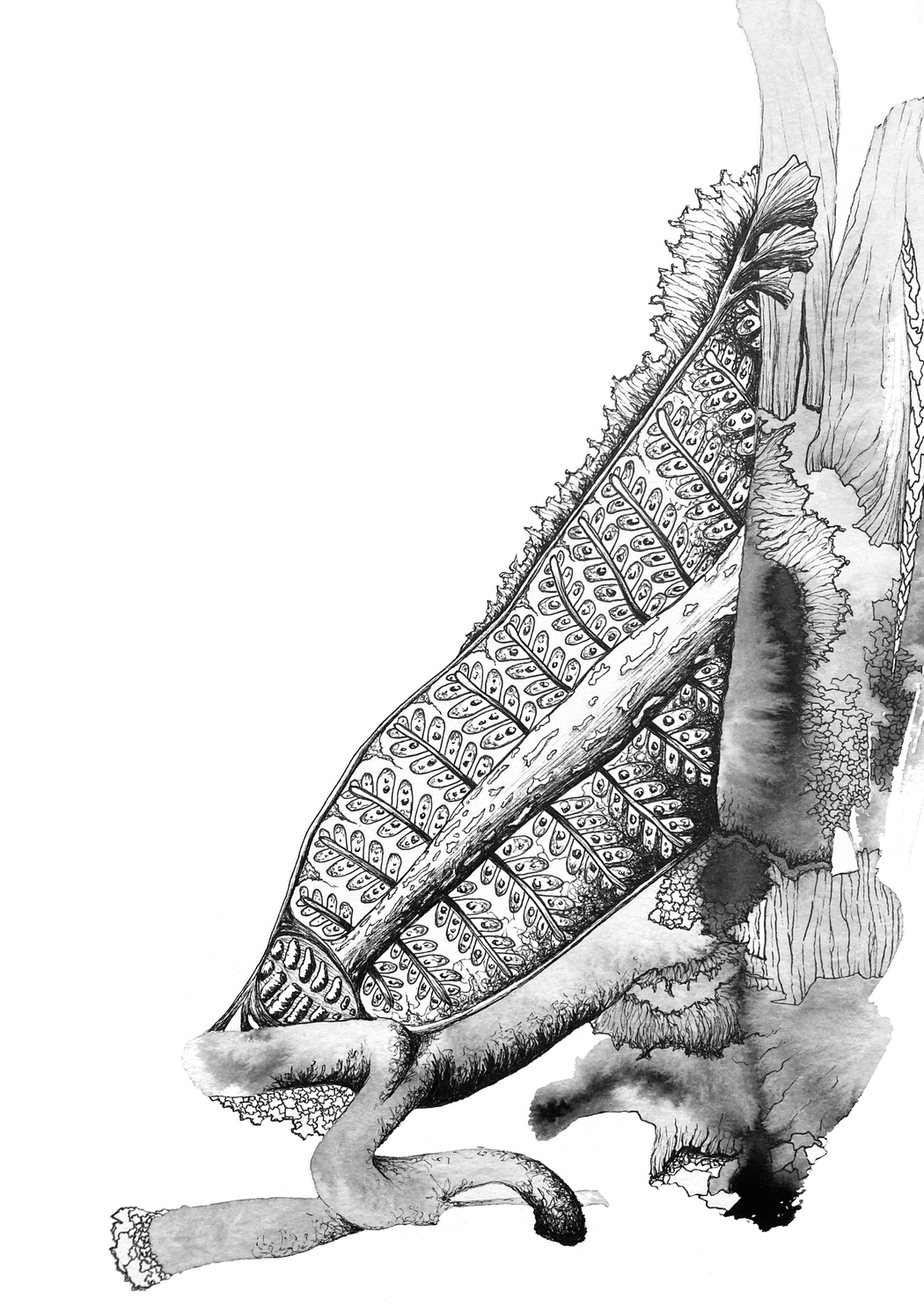

The stains made with China ink are indeed the base of my drawings. The decision of taking back control comes from a question of spatial composition. I start imagining the drawing during the staining process and begin to see shapes.

The empty spaces mean a lot to me in my work. The balance between very saturated detailed areas and empty spaces is important in order to read the image and give it room to breath. I actually stop the random stains and start drawing thinking about the space which will remain empty.

In some work, on the contrary, the surface of paper is saturated, the shape goes further than the edges of the support and its limits are not visible. In this case, the stains cover more surface and the drawing happens later in the process.

Sophie Jaffro | Micro-organique I

Sophie Jaffro | Micro-organique I

How do you personally define the balance between chaos and organization in your practice?

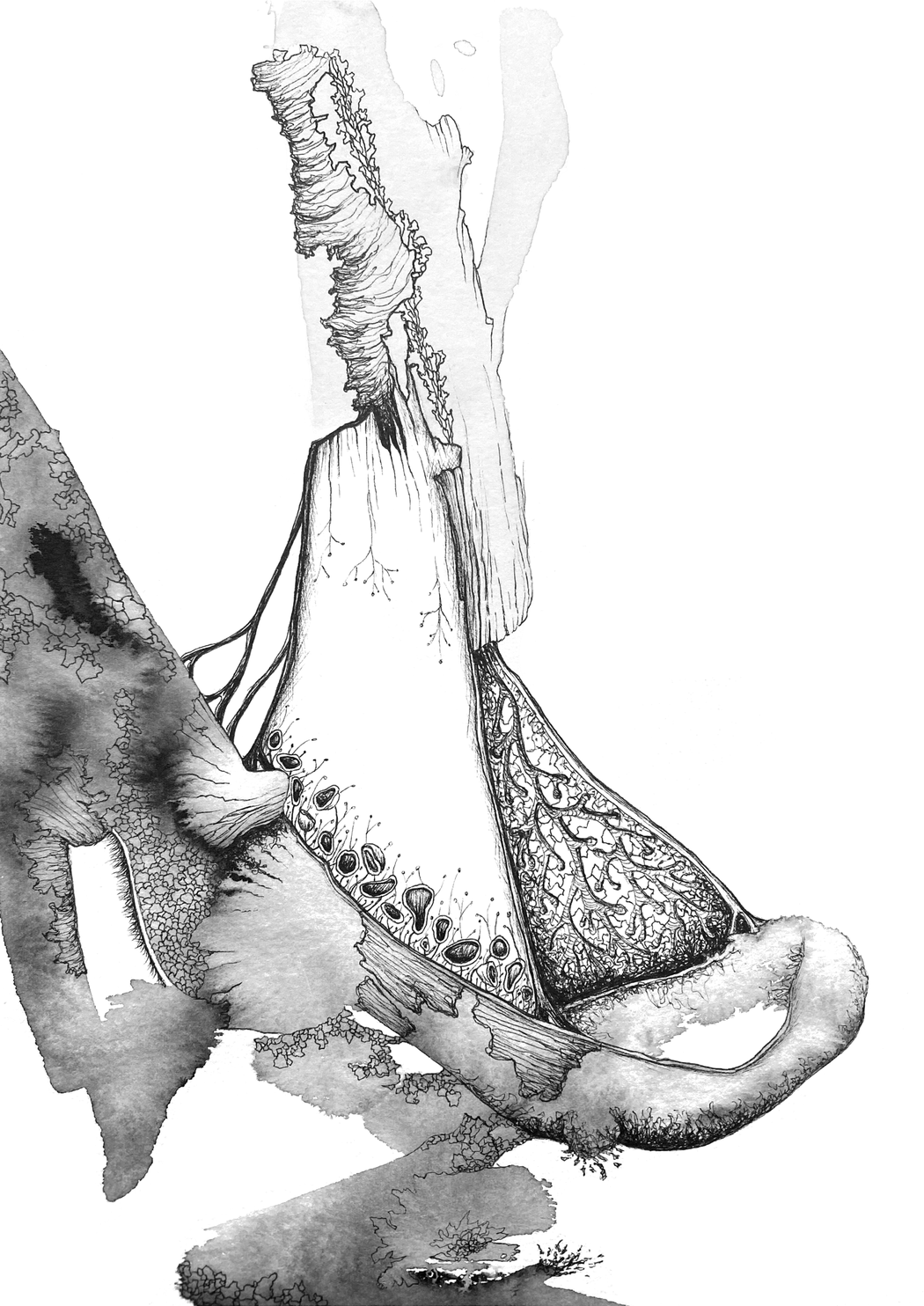

It is for me a balancing act. In my work, I’m passionate about details and realistic drawings. This way of working takes a lot of time and doesn’t allow much expressivity.

At the beginning, I forced myself to let go, to lose control and try to work in a more instinctive way. For that, I started using ink stains to generate randomness and abstraction. It is sometimes hard to set up due to the fear of failing or losing control. But it is exactly what gives birth to my work today. The chaos of the first steps of my process is uncomfortable because it’s out of my control, but it is also liberating. Creativity is no longer limited by the fear of failing, because nothing becomes an error. That allows me to create from everything, whatever happens. Taking back control with rational drawings is a way to sooth that kind of vertigo that happens with the loss of control, a way to reassure myself. That is what I also would like the viewer to feel by showing some parts of the stains, raw, untouched. The general shape of the drawing is also completely abstractive, but some details can be reassuring by looking like natural familiar shapes.

Sophie Jaffro | Micro-organique II

Sophie Jaffro | Micro-organique II

Working exclusively in black and white, what possibilities does this limited palette give you compared to color?

By using almost only black China ink, I work with the idea of scientific research. I apply a methodology, a process with limited and controlled parameters, exploring their possibilities. With the use of this protocol I explore what is offered by simple understated elements with curiosity. For that, I set constants – the use of black and white – and play with other parameters, like the wetness of the paper, the saturation of the ink and the different levels of grey, the size of the stains… Comparing the different pieces of my work shows variations, like esthetic events, thanks to the stability of these constants. However, colors tend to appear progressively in my recent work. To shake up my habits, to keep on surprising me and to feed my work. New possibilities appear, only with the way ink reacts on the paper, their pigmentation, their viscosity. The new shapes that come from it are a new parameter for me to work with.

Many of your forms evoke microscopic worlds, organisms, or imagined landscapes. Do you consciously think about scale while drawing, or does it emerge naturally?

The idea of scale often appears randomly in my work. However, there are elements that will always matter. For example, when i expand the drawing to the edge of the paper, without leaving any empty space around it, it evokes the idea that we only see a part of something bigger. In some cases, it gives the impression of flying on top of something infinite, like a map of a territory of which we only see a part. On the contrary, it can evoke a microscopic world as if you were seeing details through a magnifying glass. The interpretation is personal and depends on everybody’s perception. I often noticed that infinitely large structures and microscopic structures can look alike. Like crystals on a small scale can evoke the shape of a mountain chain, or a detail of coral can look like the overall shape of that same coral. The fractal notion in natural shapes gives this idea of blurred scales, and I think that my drawing can also be perceived in different scales.

Sophie Jaffro | Micro-organique III

Sophie Jaffro | Micro-organique III

Your process allows accidents and randomness to play an important role. Have there been moments when an unexpected accident completely changed the direction of a work?

Every piece of work comes from randomness. But there were events that led to major changes in my process. It’s often from trying concrete changes that unexpected things happen. For example, I worked for a long time on a drawing table, on a horizontal support before I decided to work by setting my paper on a wall. By putting it vertically, the shapes of the stains drastically changed. Drips and runs appeared. Lines happened in the composition, with directions. Gravity had a direct impact on what could be seen, the shape no longer expands in every direction, but from the top to the bottom. That led me to also make decisions about how to hang the piece, whether to keep the orientation that I had during the making of the piece or turn it once it’s done to play with the directions that the shapes took.

Having to work on the floor also led to important changes in my work. Because of the size of some pieces, I started putting my paper on the floor, because it simply couldn’t fit on my table. Being further away from the paper because I have to stand on top of it, the ink stains are way more expressive, splatters happen, and the drawing has to adapt. It is mainly because of technical obligations that new events happen in my work. However, in every single work there might be drips or clumsy moves that I have to accept, not as failure, but as unexpected events to work with.

Sophie Jaffro | Micro-organique IV

Sophie Jaffro | Micro-organique IV

Your work blurs the boundary between abstraction and depiction. How important is it for you that the viewer recognizes something familiar in your images?

I try to stop drawing before it starts to look like something recognizable. Even if in detail some shapes can be identified and look like natural forms, I first try to create an almost uncomfortable feeling for the viewer by not giving familiar information for the first gaze.

By this instability in processing my work, I try to lead the viewer to approach the piece not knowing what they will find in it. That is similar to my own mindset in the creative process, that I approach not anticipating what will happen.

Like the Rorschach tests, which are a series of abstract ink stains, the interpretation is free for the viewer. What the image evokes depends on the esthetic and cultural references within each of us.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.