Kareena Solanki

Kareena Solanki | Labyrinth

Kareena Solanki | Labyrinth

Your work often questions sites of sacredness. How do you personally define the sacred in today’s world?

That’s a great question. My main argument is that the sacred is defined through our tangible, physical experience of the world, even as we reach for something beyond it. The boundaries of the sacred are constantly shifting for me, leading me to question where these boundaries actually lie. I notice embodied beliefs in flux, enmeshed with daily life—like stickers of Jesus on subway trains, religious idols on streets, or the mix of traffic noise with sounds from churches, mosques, and temples. These instances inspire reflection on how the sacred and the profane intertwine in our environment and everyday experience.

Kareena Solanki | Labyrinth

Kareena Solanki | Labyrinth

In your artist statement, you mention exploring the “psychic and the political, the sacred and the profane.” Could you share a concrete example from your practice where these polarities collide?

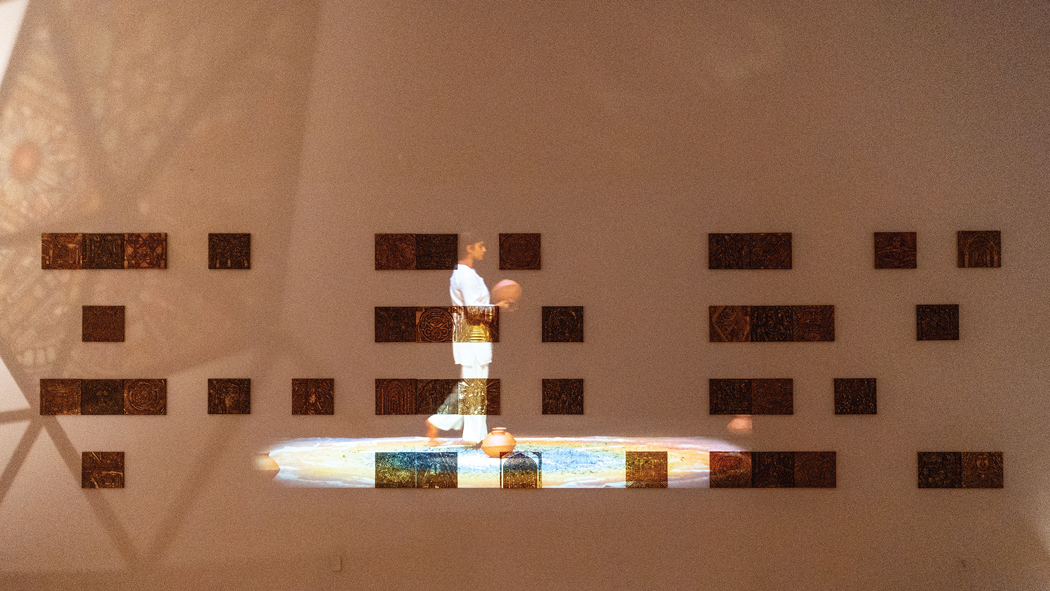

My body in performance remains the psychic medium as it draws upon improvised impulses, while its physical presence in the material world remains political. I use everyday, mundane materials – fabric, plywood, acrylic paint, and sand, which are then transformed through religious mythology and rituals in performance, collapsing the space between the sacred and profane. I question where the boundaries of definition lie. Through an interplay between materiality and process, I explore ideas of translation and transformation. The body translates into performance, artefact, sculpture and installation. The characteristics that lend themselves to these materials in different stages of ‘becoming’ are the stage for the collision of these polarities. Sand is an ordinary material, but when it is used in a ritualistic act of release through a vessel, its meaning is altered. I am interested in these moments of transformation.

Kareena Solanki | Labyrinth

Kareena Solanki | Labyrinth

Many of your works resemble rituals, both in performance and in material installation. How do you approach the creation of a ritual in your art?

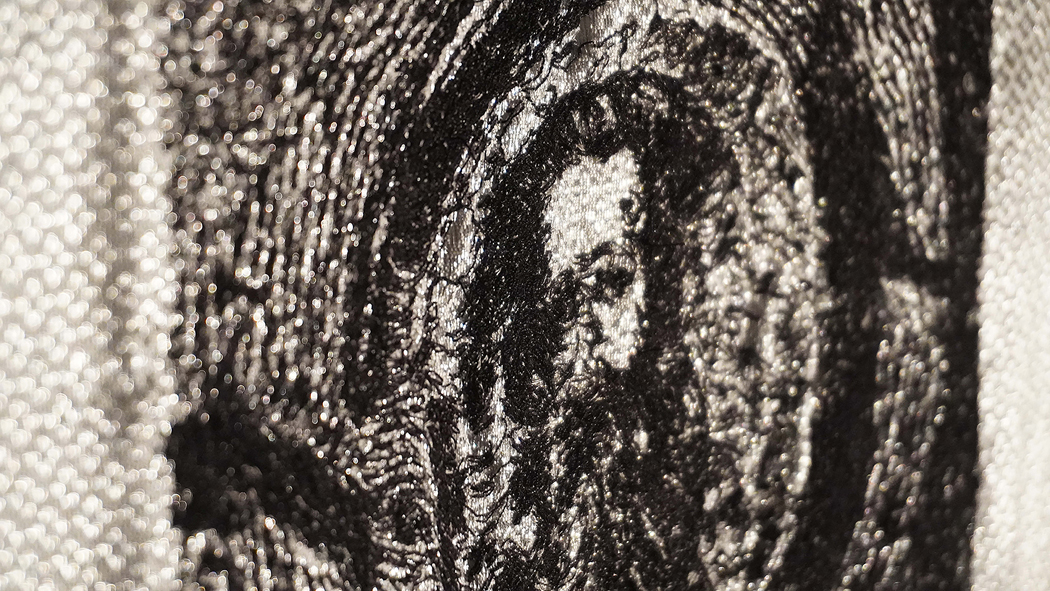

I approach ritual through daily observations of the body in space, drawing from simple gestures – walking, sitting, standing, moving in circles. I observe and question how the body interacts with its environment, which is the inspiration for a lot of the installation work. These gestures are then transformed through reflecting upon existing sacred mythologies and spiritual rituals. In Pantheon, one is surrounded by a much larger dome that envelops them, while in Labryinth, the body traverses a winding space to the centre and back out. The visitors engaging with these spaces are invited to perform their own rituals within them. For me, ritual isn’t separate from our everyday being, but is transformed through the act of awareness, embodiment and presence. Brushing our teeth, going to work, cleaning, cooking, everything is essentially a ritual in itself. A ritual is created through daily living and repetition in our everyday lives that, in turn, shapes our entire being. Stained glass, embroidery, and wood-carving have all been processes in creating sacred relics due to their painstaking, laborious, repetitive nature, which itself becomes an act of meditation. Materials in my work embody these rituals of repetition with the hand and machines, opening up space for a deeper reflection of the present times.

Kareena Solanki | Deity

Kareena Solanki | Deity

The stained-glass-like pieces evoke both mythological figures and futuristic beings. What role do mythology and technology play in shaping your imagery?

Technology to me is modern-day mythology. The images of religious symbols embedded in the stained glass works are AI-generated and are printed alongside the stained glass works onto transparency film to create faux stained glass. I intentionally generate images with imperfections and flaws through AI to reflect on the gaps in our systems. I question the role of AI and the algorithm in shaping our truths through an interplay between the original stained glass and its imitation. By doing so, I reflect upon sacred scriptures and our understanding of them. The glitches revealed in these processes allow reflection on the power that is upheld by the presumed infallibility of these systems. My work invites viewers to ponder the increasing AI-crafted myths surrounding us and shaping our beliefs, which may or may not be inherently flawed. I was inspired by a game in which we whisper into each other’s ears, and with the effects of transfer and translation, the final message is entirely different from the original one. AI too draws from an existing pool of information, remixing and regurgitating what already exists, as an intelligent language model. I question what would happen when it draws from data it has generated, and how mythology will be created through warping the original data – what purpose would it then serve? And to whom?

You speak about glitches in identity and the fallacy of immutability. How has your own transcultural experience influenced this exploration?

I always embraced my identity as being in constant flux, absorbing some impulses and releasing others. Growing up in a multifaith, multicultural environment of Mumbai, India, brought about an awareness of the multifaceted aspects of human existence and identity. During my convent school days, I recited catholic prayers at the start and end of each day. I visited hindu temples, heard muslim chants, and later began practising Buddhism. After moving to the US, I experienced an even larger ecosystem of transculturation. Acute observations about caste systems back home and segregation in the US, along with research about colonialism and its intrinsic ties to religion, prompted further inquiry into the reliance of oppressive systems on the immutability of identity. This led me to question the fallibility of these systems through glitches, revealing underlying human error and erroneous beliefs.

Kareena Solanki | Binary Text

Kareena Solanki | Binary Text

Craft and neo-craft, authentic and AI-generated — how do you balance these opposites when working with materials and technologies?

I am interested in the tensions between craft and neo-craft and how the times we live in blend both media. I intentionally introduce machine-crafted elements in my work to question the means of mechanical reproduction of belief systems. I translate AI-generated imagery onto synthetic fibres with an embroidery machine and engrave it into plywood through a CNC machine. Yet, these works are finished by hand. Through this process, I question what is lost in translation as the information goes through multiple layers of transfer and treatment. I also translate AI images onto stained glass using the Tiffany method, inserting my interpretation into an image generated through many data points, prompting questions about originality and authenticity in art.

Kareena Solanki | Binary Text

Kareena Solanki | Binary Text

Your installations create immersive environments that invite the audience into unfamiliar states. How important is the role of the viewer’s body in completing your work?

The work is incomplete without the viewer’s body within it. I create large immersive spaces with artificially generated imagery to draw our engagement from a virtual screen into a physical embodied experience. In today’s attention economy, I question the role of our physical presence and its increasing translation into a digital entity. Bringing the body into the artwork is a way of resisting a complete transcendence into the digital realm, questioning the boundaries of an ever-increasing online lived experience that separates us from our immediate surroundings. I am interested in how this duality of being fractures our understanding of self, our relation with the larger community and ecosystems. I bridge the gap between the digital and physical mediums to reflect on the impacts of our separation from our senses, continually altered by artificial means.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.