Pavel Malakhov

Where do you live: Lithuania

Your education: Leninogorsk musical and art pedagogical college

Describe your art in three words: plasticity / minimalism / human

Your artist statement speaks about the privilege of having both a body and imagination. How do you personally experience this duality when creating art?

Like many creative people, I easily slip into the world of my own imagination. Most often, while drawing, I find myself there completely. Working with what I imagine and at the same time directly engaging with the canvas, I almost stop noticing that my hand is holding a pen or that my eyes are registering everything around me – everything except the subject of my drawing. I don’t feel the fan blowing on my back or the spotlight warming my forehead. I’m fully absorbed in the work, in imagination itself. And yet, it feels incredibly rewarding to return to the body: to step outside and feel the wind on my skin, to squint against bright sunlight, or to shiver under cold rain. Having these two very different ways of existing – the inner and the outer – I truly see as a privilege. We can live both in the world of imagination and in the world of physical sensations.

Many of your works explore the human form in a stylized yet anatomically aware way. How do you balance abstraction with realistic anatomy?

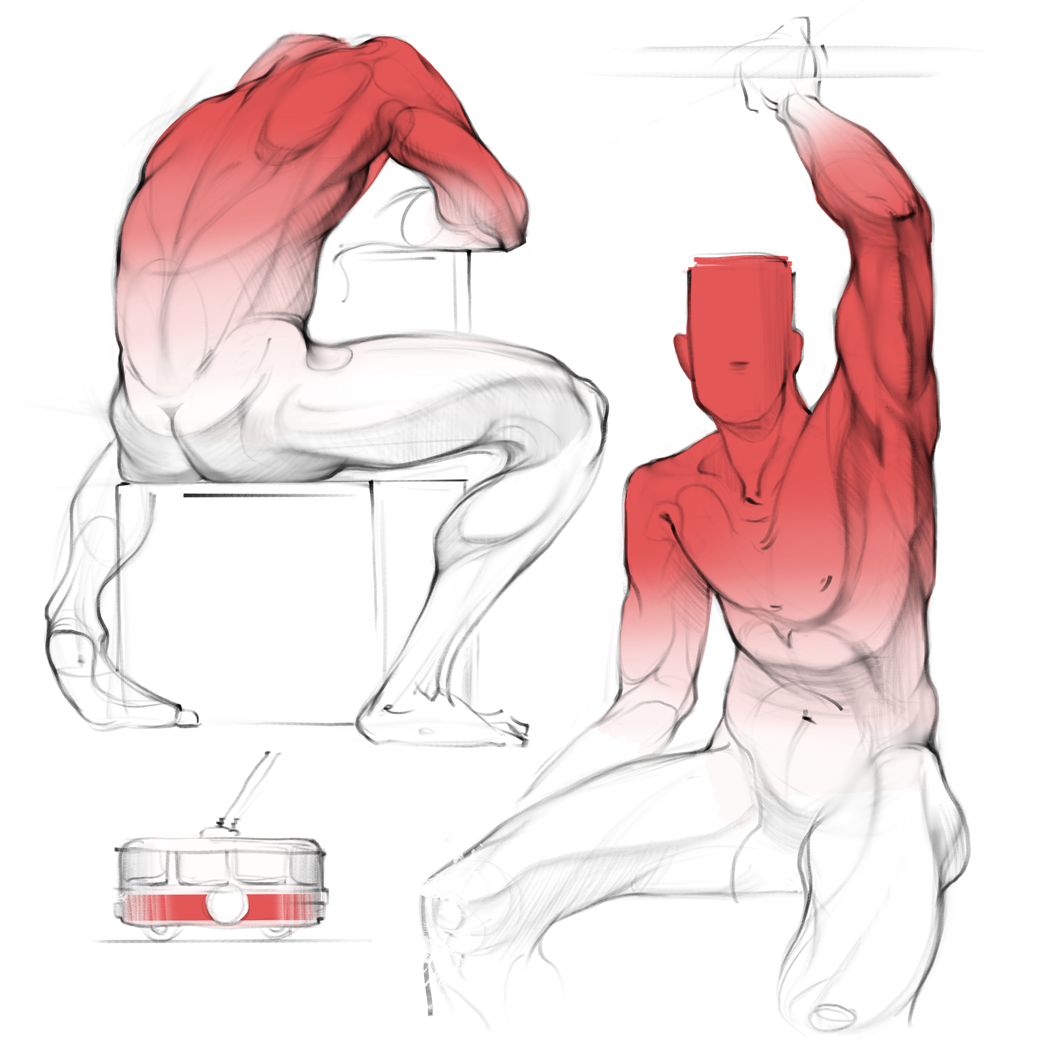

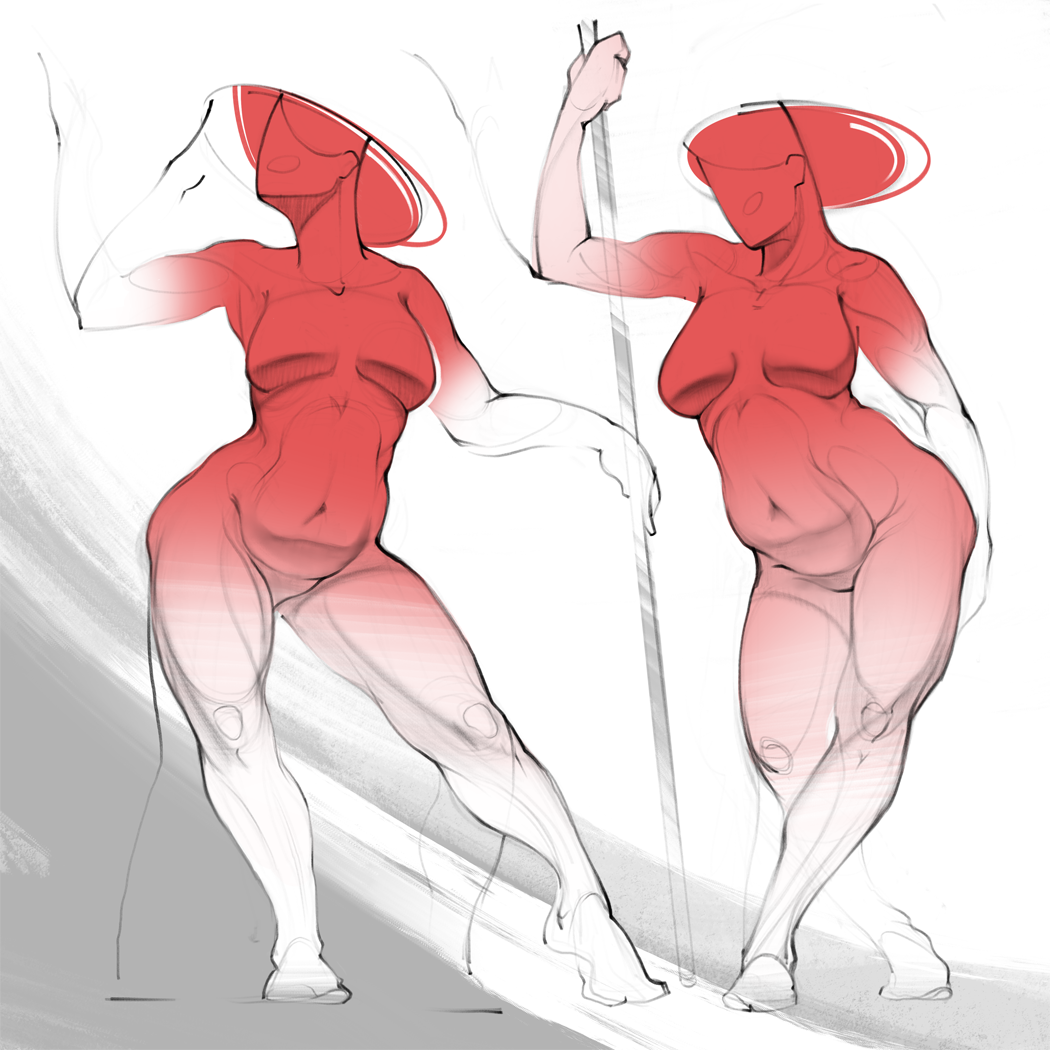

Good stylization, in my view, comes from enhancing what already exists in nature – lines that are meaningful compositionally or simply pleasing to the artist. In my own work I try not to invent but to gently emphasize the impression I see in reality. Choosing what to emphasize is not an easy process. I often rely on my inner compass: sometimes lines seem to demand to be highlighted, while others naturally recede into the background, leaving space for what matters most. Over time I noticed a pattern: I allow the most stylization in areas with soft tissue, while bony landmarks – the collarbone, knees, acromion – I try to render as close to nature as possible. This approach creates a balance between flowing, even grotesque lines and precise anatomical structure, forming a harmony of abstraction and realism.

You’ve worked extensively in the game development industry. How has that experience shaped your approach to fine art and illustration?

Above all, art for games requires structure and confident knowledge of what you’re doing. Most projects are made by teams – animators, artists, game designers – and there is no room for mistakes that could create a chain of problems. For example, an animator will struggle if a character’s proportions are inconsistent. In game art, nothing should be accidental or excessive: there should be exactly as many elements as are necessary to convey the idea, not one more. I think this practice has influenced my taste in my own creative work. I’ve learned to stop at a certain point, to accept a piece as finished. Earlier it was harder for me to know when to stop; I could endlessly rework sections, asking myself what else to add, instead of focusing on what I truly wanted to express.

How do you choose the poses for your figures? Are they more often based on life reference, imagination, or a mix of both?

I love attending life drawing sessions. In a single session I can produce 20–30 sketches of poses and movements. They may be unfinished, but they capture the living line and energy of the body. These sketches become a strong foundation: I pick the most successful ones and refine them from memory, adding elements from imagination. This method sets some boundaries and limits, but at the same time it helps me avoid slipping into entirely invented, unrealistic movements.

You mention integrating AI tools into your creative process. Could you share an example where AI helped you arrive at an unexpected result?

I usually use AI in three ways. The first, and most common, is as an assistant. It’s great at organizing files or writing simple shader code. In this case, surprises are rare. The second is for prototyping different kinds of art projects. Here unexpected results appear more often, but for me they’re not the main value. I think it’s much harder to achieve predictability with AI than randomness. Still, it can be fascinating to build something coherent out of that chaos. And the third I would call experimental research. Once I tried to build a game prototype using various AI tools: I generated images, 3D models, and code. In just a few hours, I had the first version of a game made by me together with AI. A few years ago, this would have taken much more time, and I doubt I could have done it alone. That experience was truly striking – and probably one of the most unexpected results I’ve had in recent years.

How does your background in pixel art influence your line work and shading techniques in more traditional-style illustrations?

It’s hard to judge, since I’ve never met a “version of myself” who draws people but has never done pixel art. My guess is that the influence is minimal, because they are two very different poles of visual art. Perhaps that’s why I enjoy working with plastic forms and the human figure, where lines can be sketched freely, guided by feeling. Pixel art, in contrast, demands precision, accuracy, and calculation. Maybe alternating between these two opposite styles is what allows me to enjoy both. If I get tired of one direction, I can focus on the other. This variety of paths makes moving forward easier and freer.

In your opinion, what role should technology play in the evolution of visual storytelling?

We’ve all witnessed the “inflation” of simply making a good-looking image. Just four years ago, finding a striking illustration could amaze us, and we might even thank the artist with a comment or a like. Now we live in a world where AI services can generate finished works that match that level of polish, but in much larger quantities. What becomes truly significant are works in which the artist fills the image with personal meaning and experience, using AI only as a tool. When making a “beautiful picture” became so easy, artists had to become more ambitious – focusing on ideas, messages, and the experiences they want to share with the viewer. Perhaps the era of “just pretty images” is fading, and artists will have to seek new forms of expression – including larger projects created in collaboration not only with people, but with whole teams of AI agents.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.