Paige Young

Year of birth: 1991.

Where do you live: Grand Rapids, MI.

Your education: Masters of Fine Arts, Master of Visual and Critical Studies, Bachelors of Advertising, Bachelors of Photography, Associates of Business.

Describe your art in three words: Documentary, Analog, Fine Art.

Your discipline: Photography.

Website | Instagram

What inspired you to begin working with old family photographs for this series?

When my grandfather started to decline, they began to really clean out their house in preparation of needing to move. I’ve always been fascinated with old imagery, both as a human and as an academic, so I really wanted to be the one to obtain, store and preserve these images. While I was looking through them on my own, I realized I had no idea who these people were. It was incredible to me that my family was so poor through the 1800-1900s, yet someone had access to film and camera materials. Through the late 1800s, photographic darkroom paper nor film wasn’t yet invented, meaning most of these had to be on glass plates or other mediums. In the 30’s my great grandpa Jake was also a photographer, and again, he didn’t have any more but must have had access to turn these plate images into actual photographs. However, I didn’t know most of the ‘who’s who’ while looking at these, so after my grandpa passed, but while my grandma is still alive, I took down 3 big binders of these old images and asked the stories behind them. It was then I realized that without these questions, or without any type of REAL experiences with objects handed down to us, these things passed down would just be tossed away and forgotten or put in a box somewhere and stored ‘just because.’

How did your grandfather’s passing influence the emotional tone of this project?

My grandfather means everything to me and his history was something he began to speak of the older he got. He was one of eleven kids- grew up very poor, worked on the farm before and after school and would walk 6-7 miles home after football practice. He was in charge of naming his brothers and sisters when his mother was pregnant, and when he dad got severely injured in an accident and couldn’t move, my grandfather was the one who had to step up, as a teenage, to make sure the family was provided for. He ended up also taking a liking and interest to photography, and ended up giving me my first Angus camera from the 1940s, in which he used during the Second World War. My grandfather really valued memories and photographs more than gifts and things. One Christmas in 2019 I built my own handcrafted frame and gifted him what would be our last family photograph that included my cousin, who would pass the following year of brain cancer. All unforeseen at that time, but even without that knowledge, he began to cry and told me that ’this was everything.’ I didn’t know my ancestors or my family beyond him – but I did know him and I feel his heart has always been a soft and kind one.

In “These Died With You,” how do you decide which images to include, especially when the people in them are strangers to you?

There were many factors in this. First, I had to take into account which would even transfer onto photographic paper. Some of these images are on very thick paper, others are on postcard paper, and the majority of them are on older thin darkroom paper that has to be handled with such care. I have over 300 images from 1850-1960 that interested me, but some are over exposed or under exposed. So most importantly the first way I have to choose, is the technical aspect of the photograph. Will it be a successful transfer onto photographic paper and can I make duplicates from it?

Second, character. My grandmother dove quite deeply into my great [5x] grandma and grandpa Catherine and Adam, as they were really they main characters of the story in these images. I heard a lot about them, but again I don’t know them. Their names were on a lot of things around their house too, that clearly my grandfather cherished. So I felt like I kind of knew them. The other people within the frames, their brothers and sisters, their sons and daughters, are all people I didn’t hear too much about, but the images were sometimes comical to look at [images of them getting attacked by bees, playing with water around an outhouse, and just funny images you wouldn’t think people would photograph back then, showing us we’ve always only been human]. The more these people were unfamiliar with my, you’ll see the more blurry or unable the viewer is able to identify with them. This includes leaving them as photo negatives, since our human mind would have to flip the image to make it more familiar. The images that are a bit more clearer are going to be more so the stories I’ve heard more of, or of my grandfather directly.

Can you describe your process of transferring negatives and positives in the darkroom?

To preserve the original images, I have to make copies of everything in the darkroom so I can tamper with them how I want on a larger sheet of paper. The worst part of this is being size limited and needing to cut parts of the original document off to make room for other images. I feel like everything is important, so it’s so challenging to cut out parts to tell a bigger story. First I take the original image and expose it directly onto another sheet of unexposed darkroom paper in the darkroom. This means facing the original image down onto an unexposed paper faced up [kind of like a sandwich]. My darkroom enlarger has to be on a 2.8 wide open aperture and most of the exposures range from 50 seconds to 90 seconds depending on the original paper source. After that exposure has gone through the developing chemicals, it will be a photo negative. So the next time that image is placed onto a sheet it will produce a photo positive. If I want that image to be a photo negative onto my larger sheet of 16×20 final paper, I will have to take my photo negative paper and make a positive in the same way I created the original so that way when I place it onto my finalized copy, It will produce the negative. So some of these images I have negative and positives for, so that way I can decide if I need them to be a bit more unrecognizable in my final viewing of the images.

What role does grief play in your artistic practice more broadly?

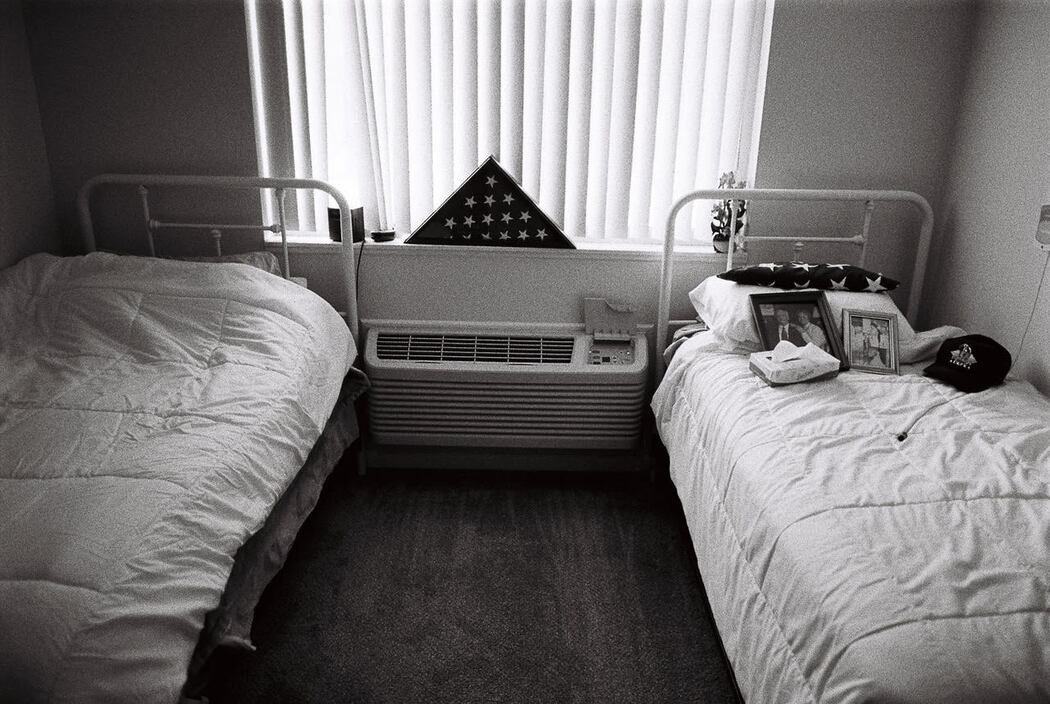

Ive been working with the concept of grief since 2019 specifically. I started when my really good friend suffered a loss of an infant of 6 months, and we decided to discuss it in visual images. After that my cousin who was more like my brother, was sent to hospice after a brain surgery went awry. I photographed what we thought were going to be his last moments in hospice with my film camera, and photographed the last togetherness between our family and him. I was inspired to create a body of work that opened this discussion of grief in which our society really stays away from, that we could all benefit from. COVID definitely amplified this project – as I ended up photographing 50 + strangers who lost loved ones unexpectedly and wanted to tell their story. This only perfected my craft and prepared me for what was to come in my life. Because of those lines of work, my series “Memories I’ll remember, Moments You’ll Forget,” and this body of work, I have learned to face grief head on, and be unafraid to play with some ideas that I would have been a bit more timid to in the past. This also comes with the topic of making work that you are a bit unaware of how your family will respond to. During my grandfathers funeral, I decided to bring my film camera and document the wake and the funeral. I wanted to photograph not just the sad moments, but the happy moments of togetherness that funerals bring us, too. I was blown away by the amount of gratitude people around me shared with me that I was documenting these moments, as I expected the complete opposite. So in a way, learning to embrace grief has made me a stronger and more brave artist. Not being scared to make work the work feels like it needs to be made.

You mentioned your grandmother told you some of the stories—how did these conversations shape the final work?

These conversations are the foundation of the work. Ironically when I graduated from my undergrad in 2013, I was already thinking about The things we leave behind. Apparently I have had a fascination with the legacies we leave behind to others for a long time. As I age I begin to think about all of the collections I have [Vinyl, 500+ Taylor Swift Enamel Pins, Photographic Cameras], and who these things will go to — if anyone? When I inherited some of my grandmother and grandfathers things and images, I began to realize I didn’t know any of the stories behind them. I could just throw them away or put them in a bin in my attic and be completely unbothered because they have no personal meaning to me since I am unaware of their value – emotionally or physically. When I took the images down to her, she told me so many incredible stories about my family, my grandfather, hardship, and other aspects of even their land that they owned that changed over the years. Without these stories, I wouldn’t have made this body of work, but also, I wouldn’t know these characters that have shaped my grandfather’s life so deeply.

Do you see this series as an act of preservation, mourning, or both?

I see this work as a bit of preservation, a bit of discussion of the humanistic quality of understanding, and mourning of specifically time passing. I love the idea of preserving these images all in one frame. They don’t have to be looked at one by one – and although you cannot see each one clearly, you almost don’t need to. You get the idea that these images are in the past, contained, and the memory of these people are fading away – just as those who are preserving them in their full memory have faded away. In discussing the humanistic quality of understanding (this one will get a bit deep), we don’t know who our family lineage really is, meaning, I hope these were good people, but the truth is in the late 1800s and early 1900s it was hard to find truly good, unproblematic, equal rights and non-racist people. So surely my great [5x] grandfather Adam fought for the north for Civil Rights, but I am unaware if he was an actual good person. So I cannot connect to him fully – because I don’t want to glorify someone I don’t know personally. But what I do know, is there is an image where I have left remotely clear in the center of one of the compositions, that he has a north uniform on, in which he took a self portrait of himself, with 3 cats on his lap, and that my friends, is something I identify with [hahaha].

Lastly, mourning time passing. As I get older, I understand I cannot stop time. I understand those around me will pass. Every year on my birthday I cry, but not because I am getting older, more so because those around me are getting older. My grandmother is not doing well, my other grandmother survived CANCER but is ever aging, my mother has auto-immune diseases that I worry about frequently, my father is doing so well but is my everything and I just cannot even handle the fact of him leaving me behind.

As I get older, my job even confirms how important documentation and photography is. These beautiful, encapsulated time in a bottle moments forever cherished. These images I have created mean something to me because they preserve my grandfathers’ life in totality. From images of when he was younger with his dog Duke [he would never stop talking about Duke when he was diagnosed with Dementia], to when he finally got married to my grandmother – these little snippets that I wasn’t there for, but through his decline I felt like I got to experience from his stories.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.