Bob Landström

Your works use crushed, pigmented volcanic rock—a very unconventional medium. What first drew you to this material, and how did you develop your technique?

Years ago, I realized that using materials closely tied to my subject could make my work more meaningful. Since then, the choice of material has been essential to me, with Earth being especially important. I feel a deep connection to it. In places where the Earth’s presence is striking, I feel this connection even more.

Take the American Southwest, for example. The deserts and canyons there radiate the Earth’s power. The vastness and sense of time in those landscapes are awe-inspiring. This connection to the Earth led me to volcanic rock. It’s a material that fascinates me with its transformation from liquid to solid, shaped by fire and air. There’s something extraordinary about it.

I started experimenting with volcanic rock as an art material decades ago. Over time, I’ve developed new ways to use it. My techniques keep evolving, and, by now, volcanic rock feels like an old friend.

Many of your themes explore scientific and metaphysical concepts. How do you balance intuitive artistic expression with scientific research?

I think art and science have a lot in common: they’re both about curiosity and exploring the unknown. A scientist might ask, “What if we try this?” or “Why does this happen?”—the same kinds of questions I ask when I create art. That process of questioning and experimenting is what connects the two.

For me, it’s not about separating intuition and research, but letting them work together. The spark of an idea can come from either direction. They feed into each other, making the process richer and deeper. It’s really about blending the two rather than keeping them apart

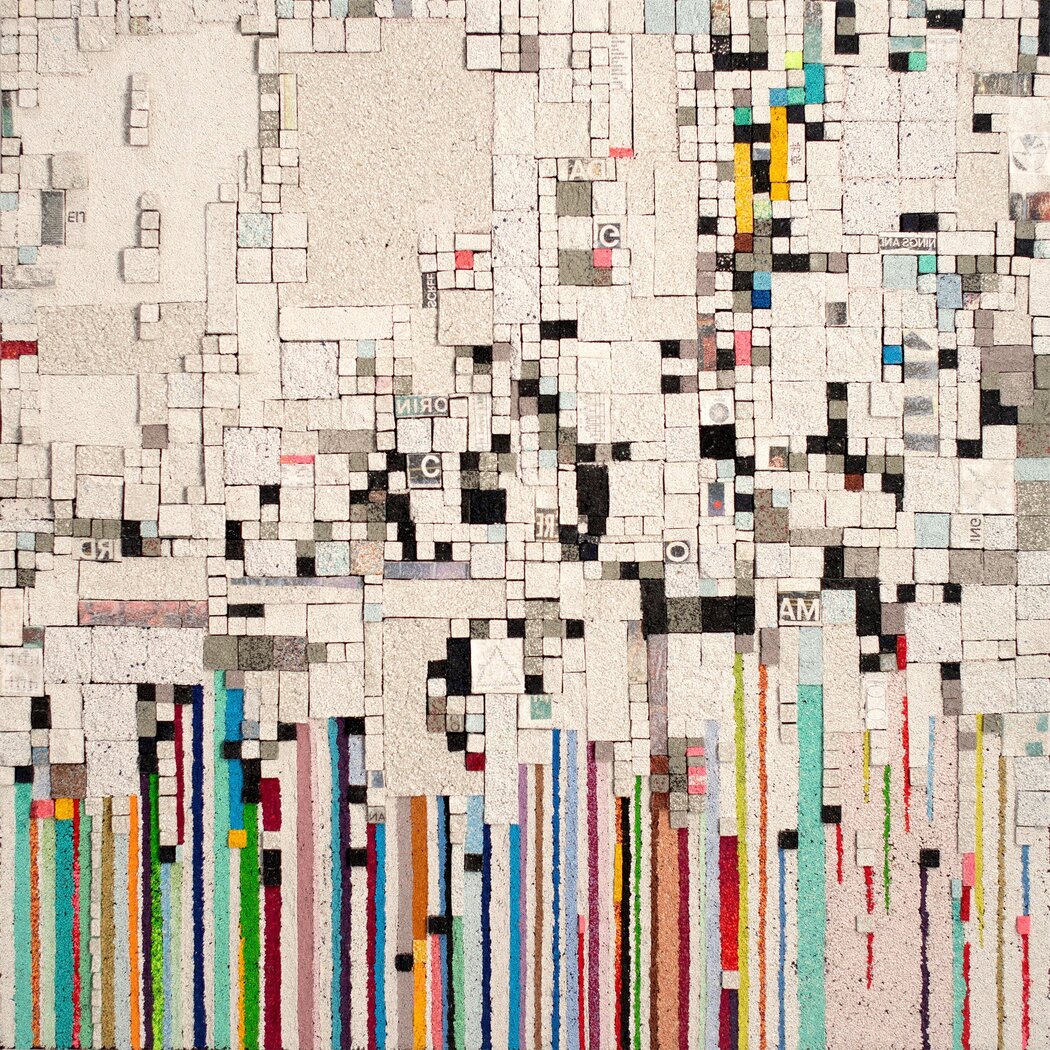

Bob Landström | Rayleigh Incident | 2024

Bob Landström | Rayleigh Incident | 2024

Can you tell us more about your process of capturing electromagnetic static and incorporating it into your visual or audio work?

Static is everywhere, it’s just a matter of how you bring it into focus. Radio is one of my main tools for capturing static. I explore the spectrum—shortwave, AM, FM—spending hours listening to and observing what happens between the channels. Some of the receivers and transmitters I use are ones I’ve built myself. Not because they’re better, but because the devices themselves are part of the artwork.

Once I’ve gathered recordings during these explorations, I take them into the studio. There, I use software like Adobe tools, Ableton Live, and occasionally custom programs in MAX/MSP to shape the raw material. The process feels like a dialogue—I’m discovering patterns, introducing structure or taking it away, and allowing unexpected moments to guide me. The surprises that emerge make this especially fun. It’s a balance of experimentation and intentionality, transforming static into something that resonates emotionally and conceptually.

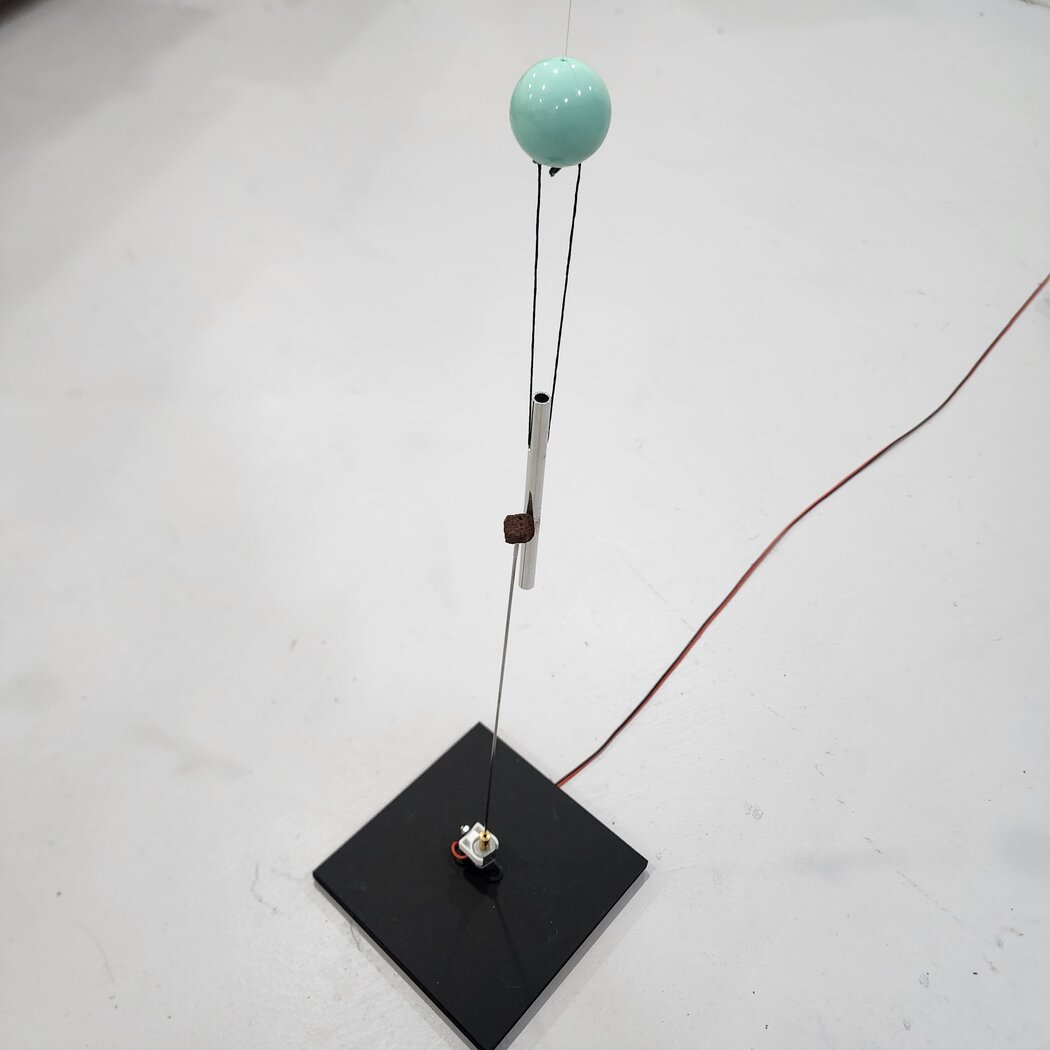

What role does sound play in your visual art practice, especially in your kinetic pieces?

Sound happens naturally when materials move together or come apart. I don’t think of my kinetic work as sound sculpture—it’s not about creating sound for its own sake. Instead, the sound’s frequency becomes significant because it relates to the materials or the choreography of the motion.

The sound is experiential, rather than about being an instrument. It’s an extension of the movement and energy of the piece, something you feel as much as you hear. It adds another layer to the work, without being the primary focus.

Bob Landström | Mercury, Installation View

Bob Landström | Mercury, Installation View

Do you consider your work to be more about the physical material or the conceptual message behind it—or is it a synthesis of both?

It’s absolutely a synthesis of both. In every piece, one informs the other. Even in my more minimal works, the inherent beauty of the material often conveys the “what” or “why” of the piece. The material and concept are intertwined, each enriching the other.

How has your background in electrical engineering influenced your creative approach and experimentation in art?

It influences my work in ways that might not be immediately obvious. Because my practice often bridges art and science, my technical background affords me a deeper understanding of the concepts I explore. When I was younger, I blamed the time in engineering classes as a distraction. Now, I see it was a complement to my studio practice all along.

My engineering education also introduced me to the beauty of mathematics. It’s abstractly and conceptually elegant. I find its visual representations captivating—even sensuous in a way.

Your paintings often evoke a sense of energy and vibration. How do you think viewers physically or emotionally respond to your textured surfaces?

Viewers definitely react to the material of the paintings. The texture can be a hook, and when they learn what the material actually is, they become loaded with reaction. It’s a unique painting medium and it seems to resonate with viewers. Not everyone gets the connection between the material and the act of art making, but many do.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.