Sebastien Theraulaz

Year of birth: 1973

Where do you live: Lausanne (Switzerland)

Your discipline: Drawing.

Website | Instagram

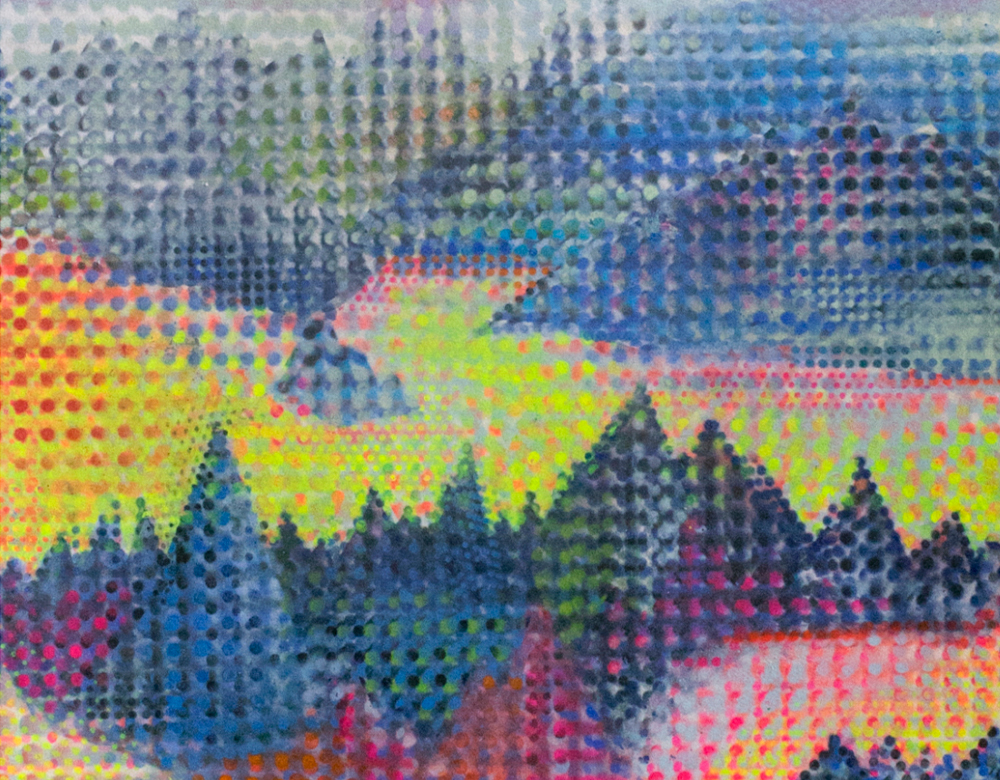

Sebastien Theraulaz | Smog

Sebastien Theraulaz | Smog

You mention that your work explores memory and temporality. Could you describe how your personal memories influence the themes and subjects of your creations?

Memory is central to my work, not as a nostalgic reflection, but as a material that can be broken down and reimagined. My personal experiences often serve as the starting point, but they are always transformed—reshaped by the passage of time, perception, and reinterpretation. Having lived in various cultural environments, I am especially interested in how recollections are influenced by place, individual stories, and collective history.

For instance, in my cyanotype series Photos d’amis, I explore the themes of presence and absence, using radiographs that evoke traces rather than fixed identities. My approach is never about preserving the past but embracing its fluidity—how it evolves, fades, and sometimes reemerges in unexpected forms.

In your project statement, you discuss mystification and the manipulation of perceptions of the past. Could you share an example of how you implement this concept in your work?

In my project Volistalgie, I explore mystification and the manipulation of past perceptions by creating collage photo prints that embrace unpredictability. I gather materials from random books, unbinding them and cutting them into fragments. These fragments, like lost memories, drift through an old neighborhood being overtaken by digital technology. I photograph these collages using vintage techniques, seeking to imbue new meaning into the images I’ve created. This approach encourages viewers to reconsider their assumptions about time, authenticity, and remembrance, as the collages evoke familiarity while remaining elusive, much like how memories constantly change.

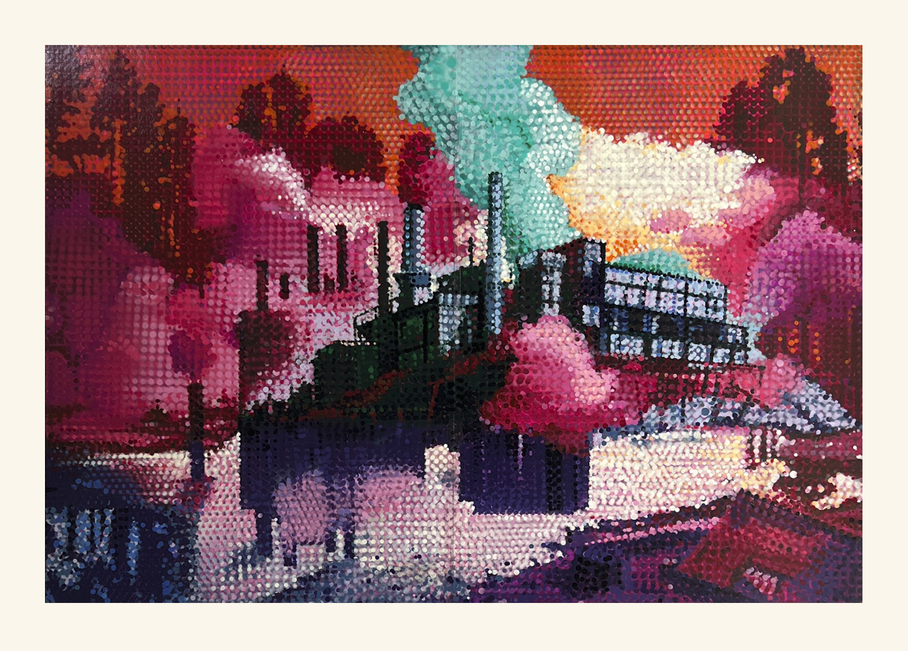

Sebastien Theraulaz | Agrogir

Sebastien Theraulaz | Agrogir

How do you balance the tension between the real and the fictional in your art? What are some of the challenges you face in this process?

Balancing the tension between the real and the imagined is essential to my practice. I view this interplay as a way to question our perceptions and the construction of meaning. My work often begins with concrete elements—found images, historical fragments, or personal stories—but these materials are then reworked, fragmented, or recontextualized to introduce ambiguity. This process creates a space where reality and fiction coexist, challenging the viewer to navigate between what feels familiar and what remains unclear.

One of the main challenges in this approach is maintaining a delicate balance: if the work leans too much toward the documentary, it risks becoming too literal; if it becomes too abstract, it may lose its connection to the real. I manage this by carefully choosing and juxtaposing elements—playing with layering, transparency, and surprising associations. Another challenge is the viewer’s interpretation: I aim to leave space for ambiguity while ensuring that the work remains accessible and evocative, rather than overly obscure.

Ultimately, this tension keeps my practice dynamic—it allows for multiple interpretations and invites the audience to engage in their own process of memory and meaning-making.

Your works appear to evoke nostalgia. How do you think nostalgia plays a role in shaping the viewer’s perception of your art?

Nostalgia is a powerful element in my work, but I approach it with a sense of ambivalence. Rather than simply provoking sentimental longing for the past, I use nostalgia as a tool to question how we form and reinterpret memories. For the viewer, nostalgia can act as an entry point, establishing an emotional connection. The aesthetic of aged textures, faded imagery, or historical references might evoke personal recollections or a sense of time passed. However, I also introduce disruptions—unexpected juxtapositions, altered compositions, or fragmented narratives—that prevent nostalgia from becoming purely comforting. Instead, it becomes something more intricate: a reflection on how memory is shaped, idealized, or even distorted over time.

By playing with this tension, I invite the viewer to critically examine their own perceptions of the past. Nostalgia in my work is not about recreating something lost, but about questioning why certain images or emotions trigger longing and how that longing influences our understanding of history, identity, and personal experience.

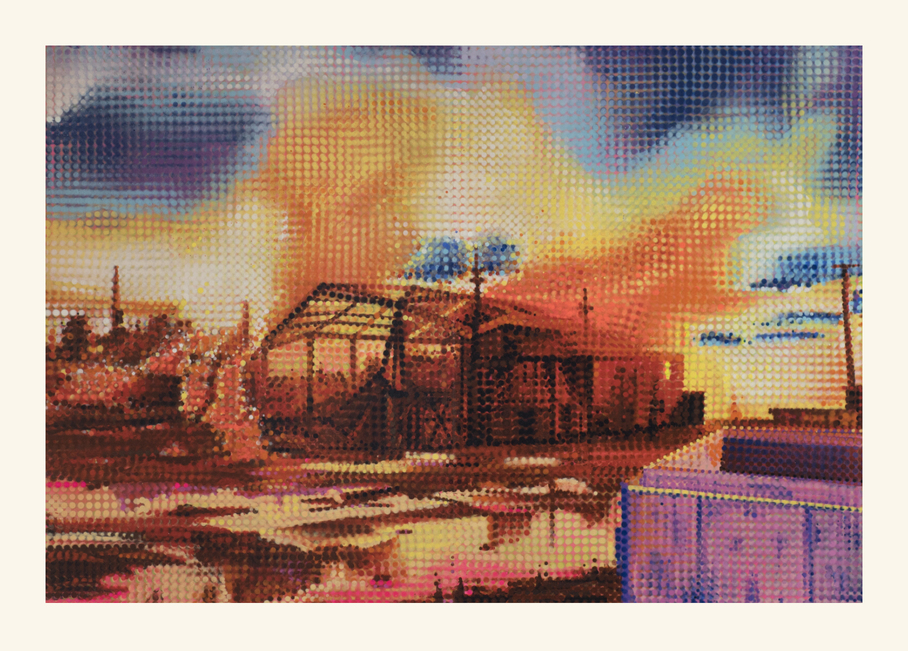

Sebastien Theraulaz | Construction

Sebastien Theraulaz | Construction

Can you tell us more about your transition from a career in creative direction to focusing on more introspective, personal art? How has this shift impacted your creative process?

My transition from creative direction to a more personal artistic practice was gradual and necessary. In my years as a creative director, I was constantly working within constraints—whether client expectations, branding guidelines, or commercial objectives. While this experience honed my ability to communicate visually and think conceptually, it also made me aware of the limitations of working in service of someone else’s vision. I reached a point where I felt the need to reclaim a space where I could explore ideas freely, where ambiguity and open interpretation were not obstacles but essential qualities.

Shifting to a more introspective and experimental practice fundamentally altered my creative process. Rather than responding to external briefs, I now start from personal inquiries—questions about memory, perception, and time. My work has become more process-driven; I embrace accidents, chance, and the physicality of materials, whether through cyanotype, collage, or mixed media. There’s also a shift in pace—whereas creative direction often demanded efficiency and clear outcomes, my artistic process now allows for slowness, uncertainty, and reflection.

This transition has been liberating, but also challenging. Moving away from the structure of a commercial environment means navigating doubt and embracing risk. However, it has allowed me to forge a deeper connection with my work, enabling me to explore themes that feel essential rather than functional. In a way, it’s a return to something more raw and instinctive—a space where I can question, deconstruct, and rebuild without predefined answers.

Your work seems to invite introspection. What do you hope your viewers take away from their experience with your art?

I see my work as an open-ended dialogue rather than a fixed statement. I don’t aim to impose a single interpretation but rather to create a space where viewers can project their own thoughts, memories, and emotions. The layering, fragmentation, and interplay between presence and absence in my pieces are meant to slow down perception, encouraging a type of visual and mental wandering.

If there’s something I hope viewers take away, it’s a heightened awareness of how we construct meaning—how recollections shift, how images deceive, and how time alters perception. My work often plays with ambiguity, inviting the viewer to embrace uncertainty rather than seeking immediate clarity. In a world saturated with fast, direct imagery, I like the idea that art can serve as a pause—an invitation to observe, reflect, and perhaps even question one’s own relationship to time and memory.

Ultimately, each person brings their own history and emotions to the experience, and that subjectivity is essential. If my work sparks an introspective moment, a sense of curiosity, or even a quiet unease, then I feel it has done its job.

Sebastien Theraulaz | Volistalgie

Sebastien Theraulaz | Volistalgie

You’ve mentioned that your art invites the viewer to revisit their own memories and emotions. Can you share how you evoke this in your pieces visually?

Visually, I work with elements that are both familiar and elusive—fragments that suggest a narrative without fully revealing it. I often use layering, transparency, and distressed textures to create a sense of time passing, of something partially erased or reconstructed. This invites the viewer to fill in the gaps with their own recollections and emotions, making the experience deeply personal. In my collage work, for example, I use images from old books and vintage magazines, cutting and rearranging them in ways that feel both nostalgic and disjointed. By removing these fragments from their original context, I create compositions that suggest lost stories or memories on the verge of resurfacing. The gaps and overlaps encourage the viewer to make their own associations, much like how memory works—imperfect, selective, and shaped by emotion.

In my cyanotypes and mixed-media pieces, I play with contrasts between presence and absence. Ghostly silhouettes, faded imprints, or traces of past imagery suggest something that was once there but is now distant or transformed. The use of deep blues, muted tones, and negative space enhances this sense of mystery, leaving room for personal interpretation.

Ultimately, I try to create a visual language that is not instructive but evocative—a space where the viewer can engage with their own past, their own emotions, and perhaps question the way they construct and hold onto memory.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.