Amy Yoshitsu

Year of birth: 1988.

Where do you live: Berkeley, CA.

Your education: AB in Visual and Environmental Studies (now Art, Film, Visual Studies) from Harvard University.

Describe your art in three words: Infrastructure, schema, deconstruct.

Your discipline: Sculpture and installation.

Website | Instagram

Your work often addresses the intersections of power, economics, labor, and race. How do you navigate such complex topics while ensuring accessibility for your audience?

Accessibility is always on my mind; I strive to create inroads for viewers through materials, colors, and imagery. In my photo-based sculptures and manipulated photos, images of publicly visible sights—city street objects, building facades, landscapes off freeways, construction zones, and industrial structures—include visuals that anyone can recognize and have associations with. I elevate these as sites of power and labor and hierarchical systems; they act as both self and collective portraits. A new viewer may react to the imagery, the scale, the movement, the busyness of a multitude of cut-outs that are twisted and sewn together. My work strives to nudge viewers to think about their own perception of their environment, their context. The Earth and what we have done on it, to it, in it, and (not often enough) with it, is what we are of.

In Inherited and Re-made, a recent installation of 84 soft sculpture words—making up 9 quotations from family members and primary source documents (Congressional speeches, historical diaries, the U.S. Constitution, Executive Order 9066, and more)—the points of entry are the many shades and tints of yellow, the softness of the objects, and the experience of walking through strings of stuffed words. When viewers slow down to take in the language made physical and learn the context, they start to understand the dialogue between global hierarchical systems and my family system.

Amy Yoshitsu | Inherited and Re-made | 2024

Amy Yoshitsu | Inherited and Re-made | 2024

Sewing and textiles play a significant role in your practice. What drew you to these mediums, and how do they help convey the emotional and systemic narratives in your work?

Sewing was taught to me at a young age by my mother and grandmother, the latter of whom was a seamstress after being Interned during World War II as a Japanese-American. I love the strength of the connection created through sewing, the conceptual value that threads provide, and that sewing, as a method, can be applied to many materials (not just fabric). As my work has become more language oriented, embodying text in its fellow language derivative, textile (from texere, to weave), reinforces the emotions, the delicacy, the flexibility, the power of our bedrock human communication system.

The properties, uses and production of textile are parallel to thinking about the systems that affect us all and how they do so on individual and interpersonal levels. Fabric, cloth, and woven objects are versatile: they can range in color and texture, be decorative, or provide infrastructure and utilitarian functions. Textiles are often associated with the body and the domestic, and have a long and continuing history in the production of objects—from local, hand sewn garments to industrialization to modern mass consumption and waste. The numerous threads that interlock to create a weave mirror how systems— language, social systems, physical infrastructural, the body—are dependent on each thread, each component, each individual.

How has your personal heritage and identity as an Asian-American shaped the narratives and imagery in your art?

My lineage drives my practice. Different threads of my family migrated to the US in the late 19th century (pre-WWI), early 20th century (between WWI and WWII), and mid 20th century (post WWII). Some of my ancestors’ assimilative experiences in the US involved being the only or one of a few in their local geography, or the struggle of always being an outsider to either world—always in-between, never in. My inheritance has been an amalgamation of internalized shame of never being enough, and a hypersensitivity to all the ways that, within the US’s hierarchical system, my assigned racial category is made a wedge between the two poles. My art practice has been the outlet for me to understand and unpack, a method towards healing. In the statement for my most recent installation, Inherited and Re-made, I wrote the following:

Quotations from family members are visually signaled through machine-sewed, single-use plastic detritus textile. I make sense of these words as expressions of intergenerational trauma, internalization of hierarchies, and the coping with confusion as a result of immigration. For example, “It’s understood” was commonly spoken during my upbringing to indicate that communication is not necessary as one should express their understanding of and love for family through enactment of expected behaviors and choices. These desires reflect the results of many strands of my lineage (the earliest starting in the 1890s) undergoing the process of assimilation—implicitly forced expeditions to discover and categorize what is normal (and not normal).

Furthermore, in Inherited and Re-made, I include quotations from Executive Order 9066 “any or all persons may be excluded” and from Article 1, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution “three fifths of all other Persons”. Because I am interested in learning and talking about the processes of creation, derivation and belief around key social infrastructures, such as race, my work often returns to the racial caste system embedded in the founding of the U.S., and in the roots of colonialism and capitalism that have become the undergirding of our contemporary context. I situate my family, some of whom were forced into Internment Camps, under EO 9066, as part of the narrative of the U.S., which began with genocide and chattel slavery. I seek to acknowledge and honor that my conditions and ancestral story are intertwined with, echoes of, and rhyme with those of many, many other humans past, present and future.

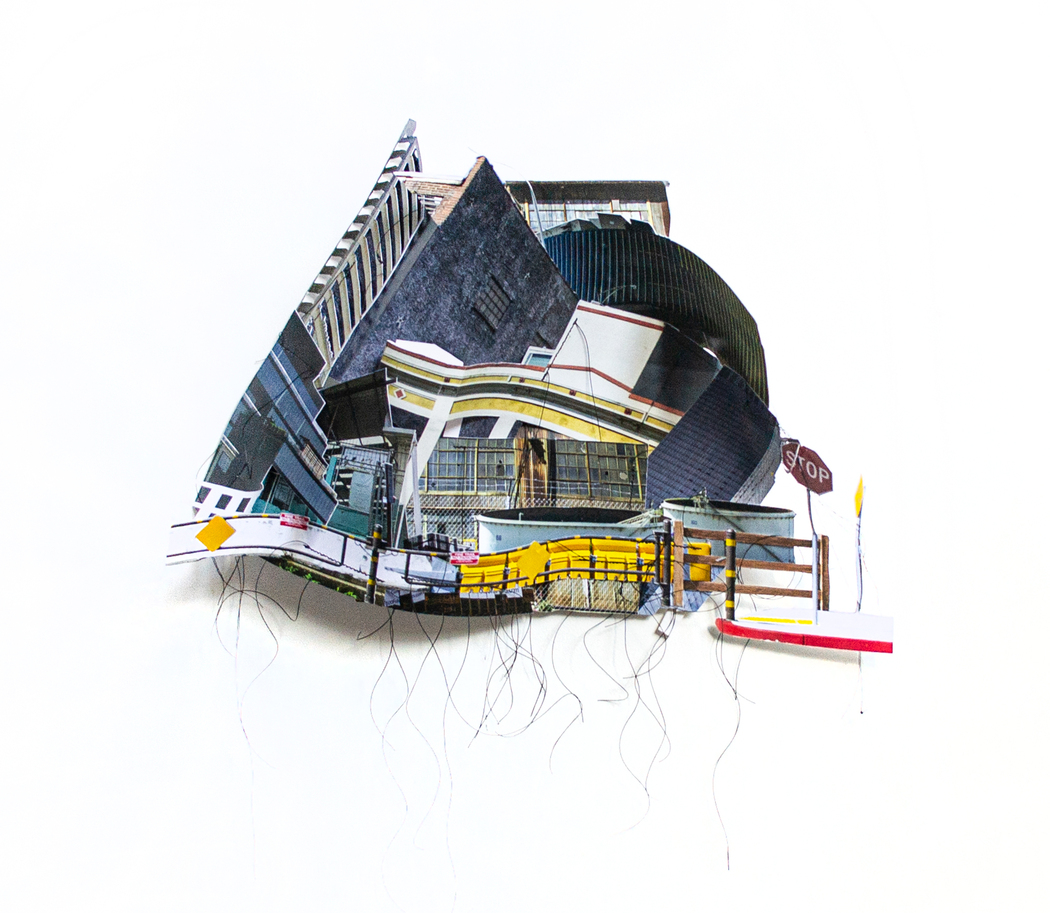

Amy Yoshitsu | No Right Way (Carquinez Bridge Toll Plaza) | 2022

Amy Yoshitsu | No Right Way (Carquinez Bridge Toll Plaza) | 2022

Your pieces deconstruct societal structures like taxation, electrical grids, and “racecraft.” What research or processes go into representing these abstract concepts visually?

Learning and understanding historical derivations are key to deconstructing social, economic, physical infrastructures. The mere existence of a creation process indicates the human-made intentionality driving control-seeking hierarchies, and the resources and effort placed into perpetuating them. I am fascinated by the histories of and theories about race, gender, capitalism and economic systems, climate denialism and its crisis, etc. I love reading and researching books, articles, primary source documents, related creations, and more, when preparing to make work about a specific topic (of the web of interconnected systems). Sometimes the research itself becomes the work.

For example, Return and Schedule Self-Interest came about from reading Dorothy Brown’s The Whiteness of Wealth, which details how the US tax system has been shaped by and is itself a tool that reinforces the US’s racial hierarchy. I started reviewing the IRS instructions and forms both from the first years that personal tax returns were required, and from the past few years. This process led me to digitally modify 2022’s Form 1040 by removing all numbers and words. Now with only lines and geometrics shapes, the forms held abstraction, repetition, and became a site of meaninglessness onto which viewers were asked to fill in the meaning. I started experimenting materially and employed sewing as a drawing tool to facilitate increased scale. The natural linen, on which the geometric pattern of the forms are embroidered, provided intimacy, creativity, a sense of fragility to government documents that are usually associated with anxiety, avoidance, dispassion and rigidity.

Your works often reflect on diasporic and assimilative experiences. What insights do you hope to bring to your audience through these explorations?

The private feelings of shame, guilt, confusion, and the mental and physical states of being isolated, can be some of the negative outcomes related to lineages and experiences impacted by diaspora, assimilation, colonization and imperialism. These painful seeds are often the initial driving forces of my projects. By expressing my perspective as I navigate the world, sharing snippets of my family history, and unpacking topics that have been the center of arguments and justifications during my upbringing, I reflect on the interconnections between my schema, and systemic hierarchies and conditions. The processes of research, experimentation and reflection, embedded in creation, gifts me a path towards acceptance, compassion, and understanding for myself and my lineage. My work also seeks to expand beyond me by integrating materials, techniques, images that ask the viewer to simultaneously think about the interplay between a subject (me, them, their loved one) and the collective within capitalism, race, the allocation and use of space and resources, and more.

Amy Yoshitsu | Mountain Arrange | 2022

Amy Yoshitsu | Mountain Arrange | 2022

How has your academic background at Harvard and CalArts influenced your perspective on art-making and critical thinking?

The requirement and ability to study from multiple fields as an undergrad at Harvard, while focusing primarily on studio art and visual studies, laid the foundation for my practice to output objects and images after digesting and integrating concepts, observations, data, and hypothesis from history, psychology, sociology, aesthetics, philosophy, economics, etc.

I am so grateful to the faculty and the visiting artists (of both institutions) who stewarded productive critiques, shared about their unique journeys, and exposed me to the approaches, contexts and choices of past and contemporary artists. These learnings have been integral to how I tackle concepts, research, materials, and how I talk about my work. Many of the artists I studied during my schooling continue to be ones that I think about a lot and that inspire my current practice: Agnes Martin, Eva Hesse, Nancy Rubins, Richard Tuttle, Gordon Matta-Clark to name a few.

My more recent works have direct conceptual throughlines to the sculptures and installations I made in my student years. In fact, I have been going back to my old creations and repurposing some of my past material choices for a series of detritus sculptures I am currently building.

Amy Yoshitsu | MomentoUS [Series] | 2022-2024

Amy Yoshitsu | MomentoUS [Series] | 2022-2024

You’ve participated in various residencies across the U.S. How have these experiences shaped your artistic development or introduced new ideas into your practice?

I deeply appreciate all the residencies and communities in which I have participated. From each residency, I have made life-long friends and art comrades. When I started to direct my focus more onto my art practice in 2020 and 2021, I did wonder if it was important for me to complete my MFA. Given the cost of formal education, I decided to throw myself instead into residencies and alternative art communities locally, nationally and online. I love that residencies can expose artists to practices of all kinds (both near and far from one’s own medium and craft); can help artists sharpen their own point of view through the process of presentations, critiques and conversations; and can help artists learn about the unique paths each creator takes based on their geographic, family and economic circumstances. Through the time, space, focus, and opportunity for studio visits during a residency, each experience has moved a series or project forward. For example, I was able to make material progress on and built a maquette for Inherited and Re-made while at Vermont Studio Center in Spring 2023. I built, completed and presented the finished version of the installation as the result of Vox Populi’s residency in Fall 2024 in Philadelphia, PA.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.