Giulia Guasta

Year of birth: 1999

Where do you live: Milan, Italy (UE)

Your education: honor BA Degree in New Technologies of Art at Brera’s Academy of Fine Arts in Milan,

actually attending MFA in Visual Arts and Curatorial Studies at NABA in Milan.

Describe your art in three words: ethical, tech, interactive

Your discipline: digital art, net-art

Giulia Guasta Guarnaccia, Server the planet, 2024

Giulia Guasta Guarnaccia, Server the planet, 2024

Could you share what initially inspired you to explore the intersection of technology and environmental ethics in your art?

My exploration of the intersection between technology and environmental ethics in my art began as an extension of my involvement in social activism, where I initially engaged with broader ethical considerations. My journey started as an attempt to map the forces at play within the technological sphere, which, by its nature, is inextricably tied to economic and political power structures. This endeavor opened my eyes to a reality vastly different from the dominant narrative of a seamlessly connected world. Challenging the unethical practices of corporations and governments, especially regarding surveillance, was my first step toward examining the environmental impact of technology and the internet. The art I try to create is openly political, grounded in a commitment to ethics—a pursuit that often finds itself at odds with the concept of development. In fact, a truly ethical approach might require us to embrace an almost unimaginable de-growth, as it would demand the dismantling of power structures and privileges. As an artist who uses technologies to talk about technologies and their impact, I make sure to use recycled or obsolete materials. For web projects, for example, I choose ethical and low-impact web hosting such as companies that use sustainable energy to power data centers. Being an activist, an artist, and a hacker, the link between technology and environmental impact became glaringly evident to me. Equally clear is the fact that these systems are part of broader structures of dominance and exploitation, encompassing everything that can be exploited, including the biosphere itself.

Your works challenge the perception of technology as “invisible” or “immaterial.” How do you approach this concept artistically?

What I try to do with my works is to deconstruct the immaterial narrative of the network and technologies, so I highlight the material aspect and the relationships that govern the narratives. Technologies are in danger of becoming black boxes, like the AIs we talk about all the time and always in an ephemeral way and not at all responsible and lucid. There is always in my installations and online projects a symbiotic or conflicting connection between inorganic and natural organic elements. Many users, especially those who come from highly technologized places, are used to spaces that tend toward the dystopian and cyberpunk. I try to re-introduce the natural aspect from which we have detached ourselves. The presence of plants and natural elements in an exhibition space greatly relaxes those who enter, and this predisposes them to stay in that space even if the themes discussed are strong.

In “Data Center[ed],” you highlight the geopolitical and environmental impacts of network infrastructure. What are the most surprising findings from this project?

Data Center[ed] is my most extensive and multidisciplinary project, especially in terms of the artistic approaches involved. One of the first insights I uncovered is that over 99% of the infrastructure powering the internet is privately owned, primarily by multinational corporations. This means that even governmental data often falls under corporate control, which I believe is crucial in conversations around surveillance and privacy. I also discovered a stark inequality in infrastructure distribution: while undersea cables and data centers are concentrated in the Global North, mineral resources are largely extracted in the Global South, shaped by geological and economic factors. The rise in extractivism is directly linked to the growing demand for data storage, highlighting disparities in privilege and marginalization. One surprising aspect is that mining locations are kept far more secretive than data center locations, which may stem from a global bias: society more readily accepts massive data centers as normalized structures, while mining sites remain less visible, even though we all know the raw materials for our devices come from these places.

Giulia Guasta Guarnaccia, Climate Evidences, 2024

Giulia Guasta Guarnaccia, Climate Evidences, 2024

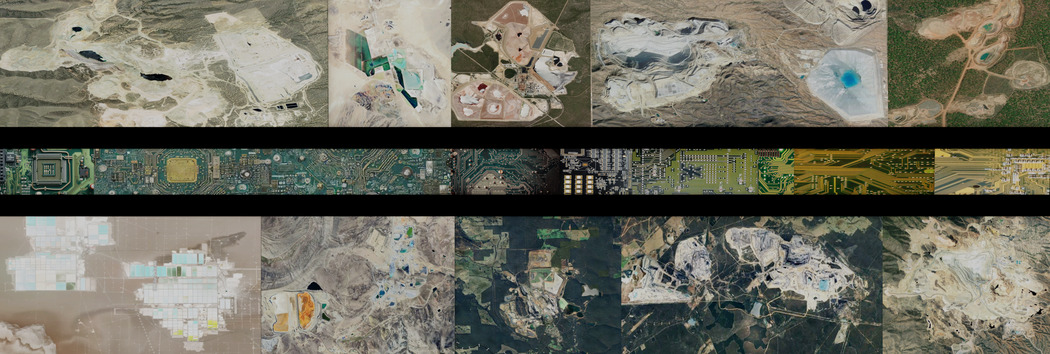

The use of satellite imagery in “Climate Evidences” adds a unique visual perspective on ecocide. How do you think these visuals impact viewers’ understanding of environmental issues?

Climate Evidences emerged as a focused exploration of the environmental impact of technology, building on themes from Data Center[ed]. Using satellite imagery—a privileged vantage point that reveals what we cannot see from the ground—was crucial for challenging the notion of technological neutrality. Satellites today serve many purposes, from research and meteorology to, most famously, geolocation. While most people associate geolocation with navigation systems in daily life, this technology has a wide array of applications, including military uses. Repurposing satellite imagery to reveal hidden realities—things present yet seldom scrutinized—is an intentional way to activate a non-neutral technology. In this case, showing images of mining sites became the most direct way for me to expose a continuous assault on the Earth, a stark depiction of the violence of extractivism worldwide. The connection to technology is underscored by a strip of recycled components like CPUs and motherboards placed between images, providing a visual link that ties these components back to the images of environmental impact.

“Server the Planet” seems to blend elements of the sacred with the technological. Can you elaborate on this choice and its intended message?

In this case, the rack structure becomes a monolith, an architectural element that encompasses several meanings. First, the usual discourse of exploiting natural elements for the sustenance of data storage emerges. Second, there is a reading of a future in which nature has taken back its own space, creating a symbiotic environment with the high-tech surfaces of the now disused servers. In this last reading, it is hoped that more sustainable alternatives to current data storage have been found. Combining inorganic surfaces with organic elements allows us to rediscover the ancient connection between the objects we produce in the capitalist system and their natural origin. The rack, losing its original function and losing its electrical and electronic life, together with plants generates another aesthetic, a less stressful perception. Some people hail technology—I know of engineers who would live inside server rooms and scientists who would never question the calculations of algorithms. At that point, it becomes ideology, an untouchable dogma, but thermodynamics itself teaches us that non-reversibility exists and is waiting for us to come.

Your works are not only visually impactful but also deeply critical. How do you balance aesthetics with activism in your practice?

I see balancing as a strong word for what I do; it’s more of a constant attempt, a risk, a willingness to push boundaries. For me, activism and art overlap; I can’t imagine art today that isn’t, at least in intent, social and political. However, the art world remains extremely elitist and not always inclusive toward themes that are still seen as too controversial. After years of protests and assemblies on issues like climate change, I felt the need to express this dissent in new ways, using art as a platform and amplifier. I’m now developing projects that are more educational, collaborative, and dialogic to encourage people to discuss these issues openly, without shame or feeling inadequate. In this sense, art for me is not only visual but pedagogical.

How do you see the role of artists in addressing the ethical and environmental impacts of technology?

Artists certainly have the freedom to explore any subject they choose, but our role shouldn’t be taken lightly—we carry a great responsibility, and it makes sense to use this platform to convey meaningful, thought-provoking content. In one way or another, artists are inevitably drawn to consider ethics, ideally leading them to act ethically as well. While it’s possible to focus on other themes, technology increasingly permeates our lives and is reshaping society as we know it. The same goes for climate change and the environmental impact of technology; it’s a topic we can choose to ignore, but it seems unwise. In addition, producing artwork is extremely non-ecological and unsustainable; just think of large contemporary art events and how much waste there is. With this in mind, artists today should try to use other materials, take advantage of recycling and recovery as active actions for ethical art. Without a planet, there will be no art, and that’s the source of the urgency I feel.

Giulia Guasta Guarnaccia, Data Center[ed], 2024

Giulia Guasta Guarnaccia, Data Center[ed], 2024

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.