Maartje Martisan

Year of birth: 1981

Where do you live: Netherlands, Utrecht region

Your education: Photo Academy, Amsterdam (2016),

NAU, Nieuwe Academie Utrecht, Utrecht (2009 / 4 years),

Orientation Year HKU, Utrecht School of the Arts, Utrecht (2008),

Health care: Nursing, Nijmegen (1996 & 2000) / Pedagogy, Nijmegen (2003) / MDFT Family Therapy, Houten (2010) / System Specialist – Therapy, Wezep (2017) / Relationship Therapy, Utrecht (2023)

Describe your art in three words: Autonomous, conceptual, therapeutic

Your discipline: Multimedia with a strong focus on storytelling, always incorporating psychological and relational elements

Website | Instagram

As both a therapist and an artist, how do these two roles relate to each other in your work? Does your therapeutic approach inform your image creation, or vice versa?

My images emerge from my subconscious, often before I can fully comprehend them. I create many images until they naturally come together. During this process, I reflect on what’s significant—what I wish to convey, informed by my therapeutic background—and sometimes, this leads me to create new images. This cycle repeats endlessly. There’s no single starting point; everything continually works together and evolves. This wholeness is what I aim to express in my projects.

Through my studies in fields such as pedagogy and systemic therapy, I’ve learned a great deal about what matters to us as human beings—psychologically and relationally. And from my studies at the art academy and photography school, I’ve gained the skills to create better-quality images, and more importantly, discovered who I am and what I want to convey in my projects as an artist.

In my work as a therapist, I see people struggle daily, often with similar issues. I feel a strong mission with my art projects to address topics that I believe are essential for achieving or maintaining mental health.

With my project Neverending End, for example, I believe that if we can break destructive family patterns, we can build a healthier, more loving society.

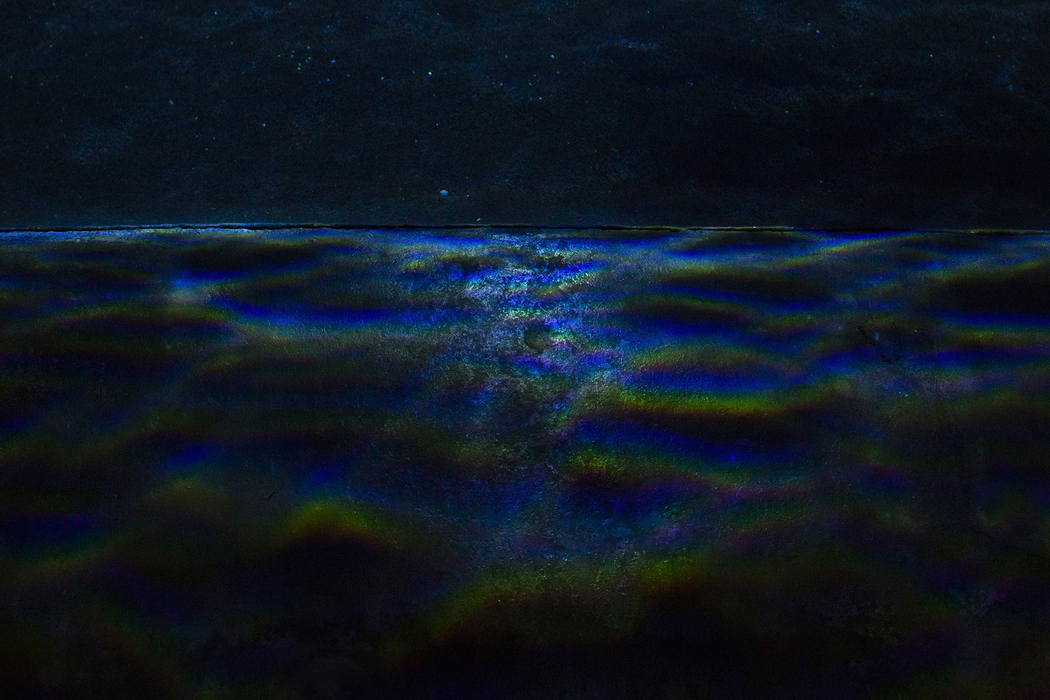

Maartje Martisan, Hope, 2022

Maartje Martisan, Hope, 2022

Your work touches on deeply personal themes, including intergenerational trauma. How have your experiences inspired you to explore this in Neverending End?

Through my own experiences—such as the anger I felt from my mother and the anger she described from my grandfather—I became determined to actively address and stop these intergenerational issues so that my own children can live healthier lives. Beneath anger often lies pain, and I chose to engage with the pain rather than the anger, which led to greater understanding and space for healing.

I’ve worked through several significant themes in my own life, which helped me process the pain rooted in trauma. For instance, I transitioned from a helper/rescuer role towards my mother, to embracing my role as her daughter, fully accepting her as she is. This shift brought immense peace to me, improving both my relationship with her and with myself. Because of the strong relationship my mother and I had, Neverending End naturally gained deeper layers of meaning.

In hindsight, I’ve been working on this project for over 10 years, though I didn’t realize it at the time. I always work from a place of feeling, from my subconscious. Only in the final year of my photography studies did everything come together. I realized then that all my work from the art and photography academies centered around the same theme: my desire to visually explore my sense of disconnect. This disconnect, I discovered, stemmed from intergenerational trauma—a cycle I’ve since broken.

You describe internalizing your mother’s trauma and ultimately finding peace. How has this personal journey influenced your artistic practice?

Recording my interactions with my mother—through audio, video, and photography—made me acutely aware of this process, deepening it further. Both my mother and I are creative, leading to many ideas we could develop and explore together while she was still alive. This strengthened our bond even more.

Maartje Martisan, Disappear, 2022

Maartje Martisan, Disappear, 2022

In Neverending End, you aim to confront uncomfortable emotions and disconnection. How do you think audiences typically respond to these themes in your work?

Audiences often tell me they feel a sense of recognition. During exhibitions or lectures, people openly discuss their own struggles and patterns. My artist talks have sparked beautiful conversations about self-reflection, and meaningful exchanges about ethical issues such as trauma, mental health care, and assisted suicide. These dialogues have been invaluable.

How do you balance exploring such heavy emotional themes in your art while maintaining your own mental and emotional well-being?

Thanks to my work as a therapist, where I deal with difficult themes daily, I’ve learned a lot. I firmly believe that life isn’t easy, and we must accept that. It’s normal. I’ve embraced this, which makes life feel less heavy. I also take good care of myself by focusing on my health and doing things that energize me. For instance, when I create an image that feels just right, I gain a lot of energy from that.

You’ve mentioned your focus on preventing the transmission of intergenerational trauma to your children. How do you see your art contributing to this goal?

Through my images or artist talks, I hope people become more aware of their own disconnection. This awareness can spark an inner dialogue, prompting individuals to process difficult situations more deeply and find acceptance. This is the first step in stopping destructive patterns and creating a better life.

Maartje Martisan, Portrait my mother and me, 2022

Maartje Martisan, Portrait my mother and me, 2022

Can you share more about the role your mother, Cornelia, plays in your work? How did she feel about being the subject of your art?

For my mother, this project was extremely important. She wanted the world to know more about the laws and regulations surrounding assisted dying in Switzerland. My mother went to Switzerland because she couldn’t get assisted dying in the Netherlands. She wanted people to understand that they don’t have to commit suicide if they genuinely wish to die, sparing themselves and others additional trauma. Her last wish was for people to realize there is a place in Switzerland where you can die with dignity, surrounded by loved ones.

I am deeply motivated to share this project with the world, both for the new generation—to help them grow up healthier—and for those who seek a humane way to die, in alignment with all ethical considerations and legal frameworks.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.