Tiffany Duong

Year of birth: 2002.

Where do you live: Toronto.

Your education: OCAD University, with a BFA in Drawing and Painting and a minor in Illustration.

Describe your art in three words: Whimsical, Vulnerable, Immediate.

Your discipline: Fine Arts and Illustration.

Website | Instagram

Your work often features melancholic dreamscapes. Can you tell us about the inspiration behind this particular aesthetic?

My work is fueled by the choppy, hazy nature of memory, and I take on a photomontage-like approach in composing my work. Movies such as Wong Kar Wai’s “Fallen Angels,” “Trainspotting,” and Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s “Millenium Mambo” are big influences for me in the way that they visually capture the act of recollection: raw, bittersweet, and tinged with the rose-tinted glasses of nostalgia. While my works are not always collages, the manner in which I juxtapose images take inspiration from dadaists and surrealists and I enjoy using transparency to convey how memories overlap, are recalled, and eventually recede into one’s subconscious. While the melancholic aspect of this aesthetic draws upon the complex emotions attached to one’s memories, I consider my works as “dreamscapes” because they seek to present and preserve parts of our finnicky memories as fleeting moments which can no longer exist, besides within an ethereal realm.

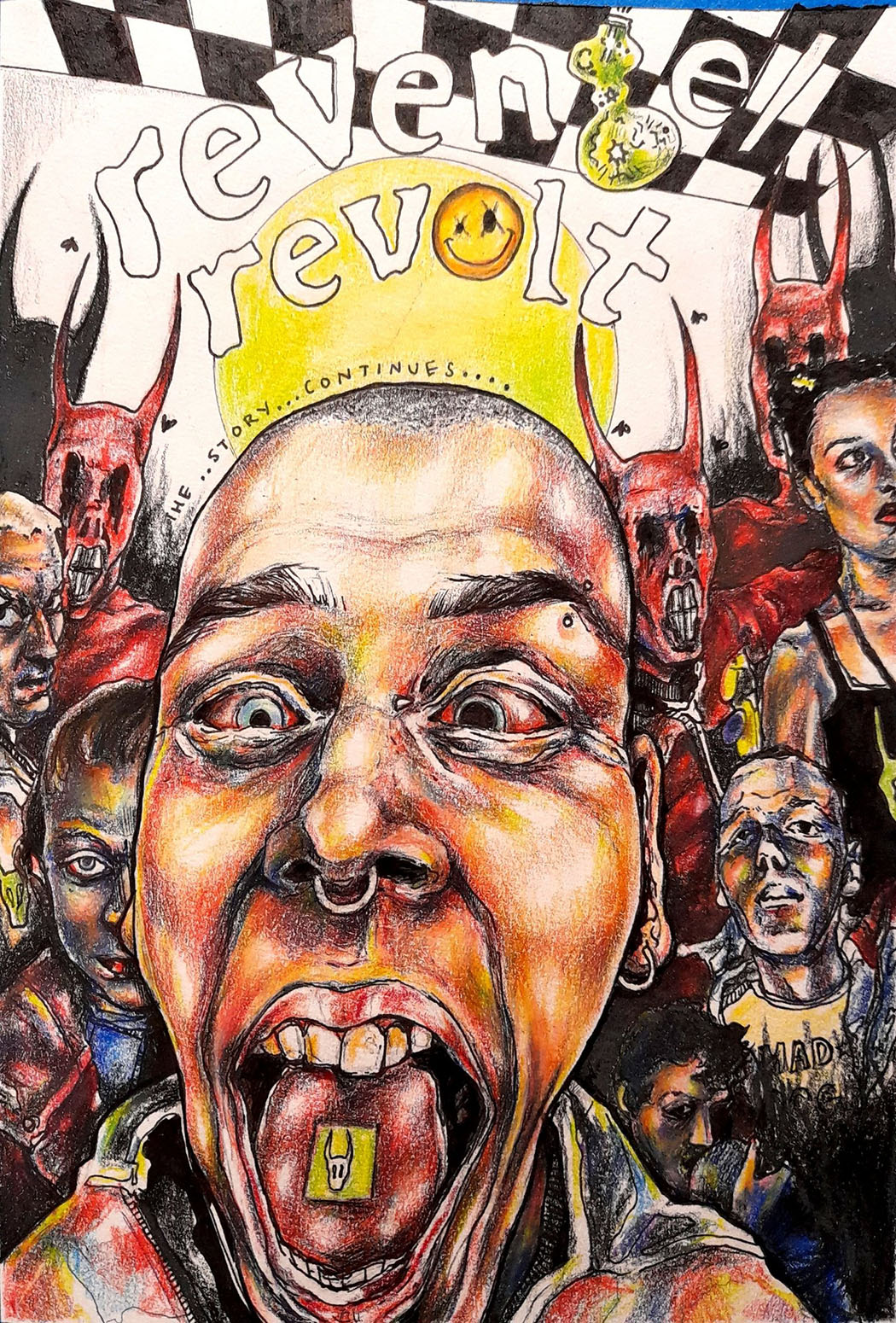

Tiffany Duong | Revenge/Revolt

Tiffany Duong | Revenge/Revolt

How do fairy tales and folklore influence your art, and do you have any favorite stories that you draw from?

Fairy tales are often thought of as a way to instill moral values in children in a manner that attempts to be both grounded in, yet distant, from reality. The absurdist nature of these stories, alongside their didactic depictions of good and evil, can be used as vessels for explorations of the human condition, which are always more complicated than fairy tales make it out to be. However, I find that the inherently inconsequential world, whimsy, and ridiculousness of fairy tales allows my work to find humor in itself and the world – to make the mundanity of reality feel fantastical. As such, my favourite story is Alice in Wonderland. I find that, as there isn’t really a clear moral story, it can be interpreted in and applied to so many different aspects of our lives. Its escapist undertones, or Alice’s shame and struggle with her size,, for instance, hold true to my own perspectives towards my womanhood and girlhood. It veers from traditional children’s storytelling in a way that allows it to remain relatable in my adult life, and affects that manner of storytelling I take on within my own practice.

You mentioned that your work is like a diary. How do your personal experiences shape your art?

Growing up, my mom would read through my diary. She would confront me about things I’d written, and from then on I could never write freely, knowing nothing could be private. I had to find a different outlet – one that would not be accessible to her – and was drawn to the idea that my work could be protected by symbolism. As such, every atom of my experiences influences my work: my joys, discontent, rage, mundanity – I consider my work as a way for these feelings to take form in secrecy, without consequence. In my artworks, I am liberated to both construct and dissect my experiences as a woman in the contemporary world. Furthermore, as diary-writing is something that I largely associate with my childhood, the themes of nostalgia, girlhood, and memories prominent with my art are perhaps a result of the diary-like manner in which I approach the art-making process.

Tiffany Duong | Packing Is Almost Done I Think

Tiffany Duong | Packing Is Almost Done I Think

Your project “Packing is almost done, I think” addresses the standards set by patriarchal structures. Can you elaborate on the emotions and thoughts that drove this project?

This piece was inspired by a text from my friend, who was packing for a family vacation abroad. I’d asked her how her packing was going, to which she responded: “Packing is almost done, I think.” As a woman, I find packing to be a stressful task because I feel obligated to bring so many things with me to maintain societal standards of beauty, and the defeat that tends to come with the nature of packing could be expanded and exaggerated to reflect on my taxing existence as woman within patriarchal contexts. I wanted to use the humour of packing a tiny suitcase to represent this in a relatable manner, and the project allowed me to put my old doll clothes and 1998 Barbie carry case to use, which allowed me to deal with my frustration in a playful and cathartic way.

How do you balance whimsy and humor with the serious themes of womanhood and human relationships in your work?

As I am not drawn to wholly realistic representations of life and the world, I use notes of fantasy and absurdism to balance the serious themes of my work. Imagery from fairy-tales, for instance, is very common in my work as the childlike wonder associated with these stories allow my investigations of bleak experiences to take shape defiant of its grim situation. I find the distortion and subsequent separation of these experiences from the world as it exists, governed by physio-chemical and spiritual laws, can be used as a means to deviate from demands to adhere to reality, bringing forth a sense of mischief and frivolity to my work.

How do you think your work challenges colonial and patriarchal narratives in society?

As my work is intrinsically involved with my experience as a woman within the patriarchal structures of Western culture, I use art as a means of allowing myself to take up space and by extension, insert the validity of my existence through the dominating, almost monstrous, scales of my female figures. In doing this, I reject the ideals of feminine beauty, amplifying the grotesque and bastardly. Meanwhile, my works on memory are significantly tied to my relationships with my female friends and family members, especially my mother. Despite the various experiences with womanhood, these connections are all linked to the fact that my reality, as a woman’s, will never be liberated to the sense of man’s being-in-the-world: the patriarchy stands to reject my humanity when I am always doomed to the gaze of the Other, reduced to objectness. Since a lot of women share this experience, I want to emphasize the beauty and warmth of these relationships in spite of how women are pitted against one another.

How has your background and life in Toronto influenced your artistic journey?

Toronto is flawed. VERY flawed. And perhaps it is this total lack, or even rejection of perfection, that inspires the experimentation of my work. I used to have an idealised vision of this city, and while the diversity and strong sense of community here has definitely assured me in my pursuit of artistic ambition, the rapidly changing landscape has inspired me to be more mindful of my memories and experiences, which fuels my practice. It is difficult to long for something that you briefly encounter, and futile when you know that its destruction is permanent, but there is beauty in the hubbub.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.