Vito Antonio Lerario

Many of your portraits feel theatrical, almost staged. How important is storytelling and dramaturgy in your figurative works?

The theatricality in my portraits is not accidental, but a deliberate choice born from my direct experience in the theater. I’ve worked on building identities in the theater, and this has taught me to think in terms of paintings, in terms of dramatic compositions.

Dramaturgy is fundamental to me: every portrait is a stage photograph. I work extensively on composition, on light, which is my primary narrative tool.

However, my theatrical approach remains spare, free of frills. I believe in essentiality: by eliminating the superfluous, I can get to the heart of a person’s identity, to what I truly want to emerge.

This search for essence has taught me to trace the power of images with just a few strokes, creating a strong visual impact. I don’t want to decorate or embellish—I want to delve into, reveal. “Staging” paradoxically becomes a way of stripping away, to reach the subject’s truth through a few powerful and necessary elements.

You work across many fields – fashion design, tailoring, photography, illustration, performance, and curation. How do these disciplines inform and enrich one another in your practice?

I’m a multifaceted person by nature, and I believe this multiplicity isn’t a source of dispersion, but rather a source of enrichment. All the fields in which I work—fashion design, tailoring, photography, illustration, performance, curation—are deeply intertwined and constantly interact in my practice.

This interdisciplinarity allows me to have a comprehensive vision of aesthetics: I can curate every aspect of an image or project, from costume construction to lighting, from performative gesture to visual composition. I never have to delegate my vision; I can control it entirely.

The result is images that appear constructed—because indeed they are, in every detail—but which at the same time emerge naturally. This naturalness comes precisely from the fluidity with which I move from one discipline to the other: they are not separate compartments, but different tools of the same language.

Tailoring teaches me precision, photography composition, illustration the synthesis of the sign, performance the body and movement, curation the overall view. Everything comes together in a single artistic vision.

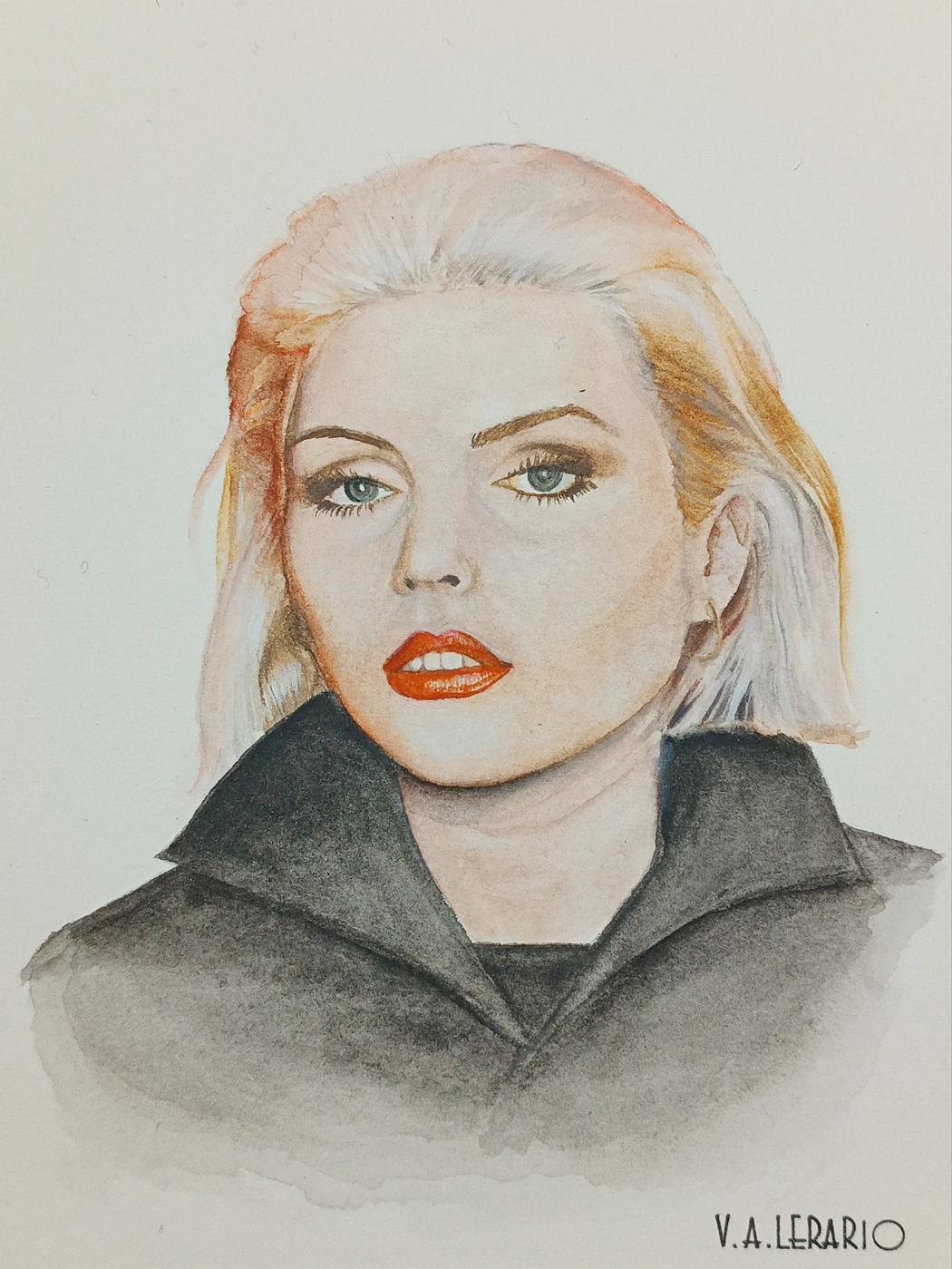

Vito Antonio Lerario | Blondie

Vito Antonio Lerario | Blondie

Fashion illustration plays a central role in your career. What can fashion teach contemporary figurative art that traditional fine art sometimes overlooks?

Fashion can teach contemporary figurative art a great deal, especially an attention to detail that is often overlooked in traditional art.

Clothing is a fundamental part of a subject’s, a person’s, identity. It should never be overlooked because the color of a garment, the shape of a garment, convey very specific messages. Even in works of art with the most essential compositions, the clothing worn by the portrayed subject certainly has an impact on its shape and color—it shouldn’t be overlooked altogether, because these elements also communicate precise messages to the viewer. Fashion illustration has taught me an almost obsessive precision: every detail counts. The drape of a fabric, the way light strikes a surface, the relationship between body and clothing, between form and material—these elements are not embellishments, but a true language.

I am convinced that in contemporary art, the attention paid to clothing is fundamental. All artists should pay more attention to this, because neglecting clothing means losing a very powerful narrative tool for expressing the subject’s identity.

Vito Antonio Lerario | Elvira

Vito Antonio Lerario | Elvira

Your watercolor portraits, especially of women, balance technical rigor with emotional intensity. How do you approach the tension between control and spontaneity?

Watercolor is a technique that by its very nature imposes this dialogue between control and spontaneity, and it is precisely this tension that fascinates me.

The technical rigor in my work stems from my training: my background in design, in the construction of clothing identities, and in fashion illustration have taught me precision, the ability to plan every element. I approach watercolor with a clear idea, with a careful study of composition, light, and volumes.

But watercolor is unforgiving—and doesn’t allow you to control everything. There comes a moment when you have to let the water, the pigment, and the paper dialogue with each other. You have to accept the unexpected, the unpredictability of the material. And it is precisely in this space, between what I planned and what happens spontaneously, that emotional intensity is born.

In female portraits, I always seek this truth: a balance between rigorous structure—the shape of the face, the anatomy, the light—and the free, instinctive gesture that captures something ineffable and intimate. Control gives me form, spontaneity gives me soul.

It’s a precarious balance, but a necessary one.

Vito Antonio Lerario | Fuga a Notre Dame

Vito Antonio Lerario | Fuga a Notre Dame

As a teacher at Ideacademy in Bari, how do you encourage students to find their own balance between formal discipline and expressive freedom?

As a teacher at Ideacademy in Bari, I try to pass on to my students what I’ve learned from my practice: that discipline and freedom are not opposed, but rather nourish each other.

I always start with the technical foundations—drawing, understanding anatomy, studying light, and knowing materials. I firmly believe that without a solid formal discipline, there can be no true freedom of expression. It’s like learning grammar before writing poetry: you need to know the rules to then adapt them to your own personal language.

But at the same time, I encourage my students not to be afraid of mistakes, the unexpected, or instinctive gestures. I push them to find their voice, to understand what they want to say through images, what identity they want to build or reveal.

Every student has a different balance: some need more structure, others more freedom. My role is to help them recognize where they are and where they want to go, providing them with the technical tools but also the confidence to experiment.

Ultimately, I teach them the same process I experience every day in front of paper.

Vito Antonio Lerario | Theda | 2026

Vito Antonio Lerario | Theda | 2026

How has teaching influenced your own artistic practice and way of thinking about image-making?

Teaching has profoundly transformed my way of working. It forced me to verbalize processes that were intuitive to me, to make conscious gestures that I used to make automatically. When you have to explain to someone why you choose a certain light or how you construct an identity through clothing, you are forced to question your own method.

This has made me a more aware artist. I learned to look at my work with different eyes, to recognize my stylistic choices, to understand where my aesthetic comes from. Teaching is a form of continuous self-analysis.

Furthermore, students constantly challenge me. Their questions, their points of view, even their mistakes, open up new perspectives. They force me to take nothing for granted, to question established certainties. It’s a precious exchange: I pass on technique and discipline to them, and they restore freshness and curiosity to me.

Teaching has taught me to be more rigorous in my work, but also more open. It’s a dialogue that enriches both parties.

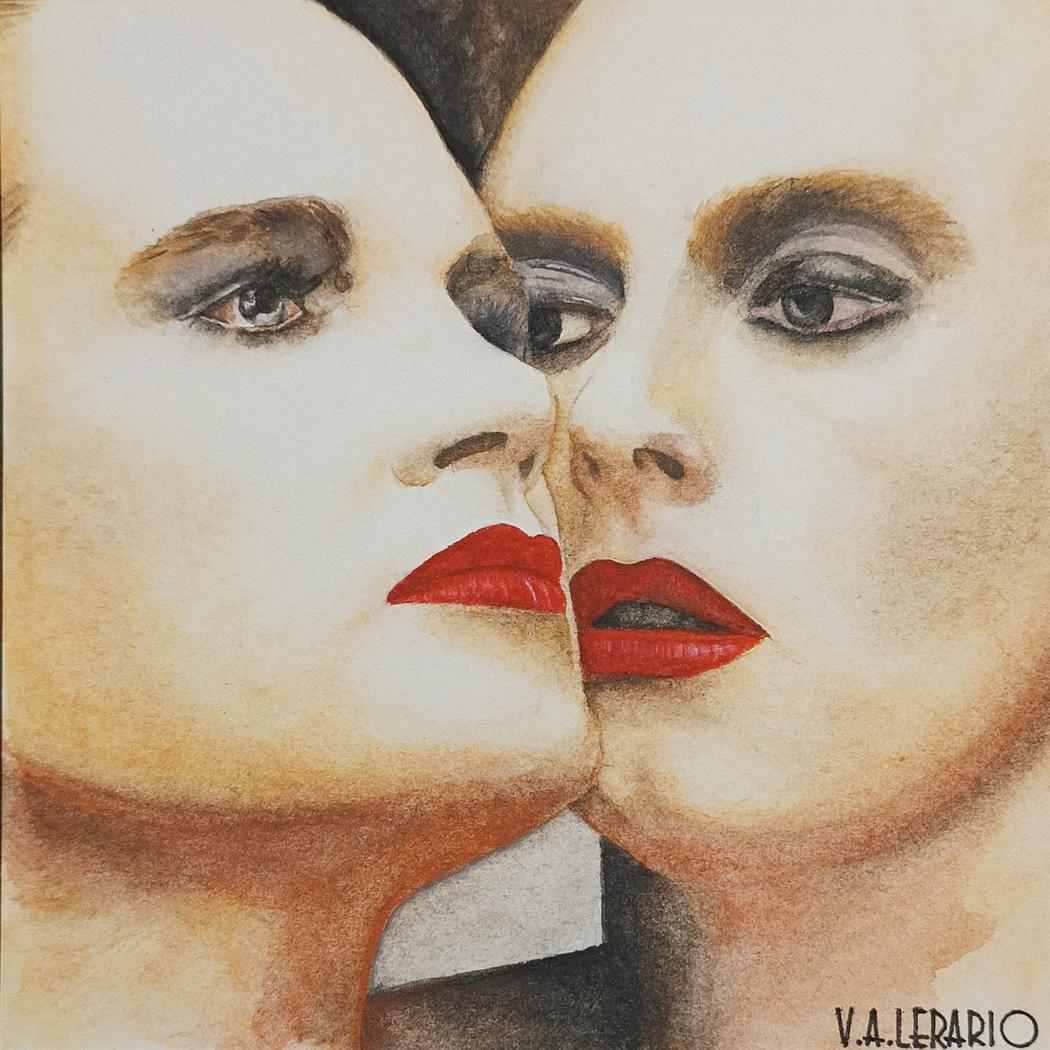

Vito Antonio Lerario | Virgin Prunes

Vito Antonio Lerario | Virgin Prunes

Your work often explores metamorphosis – physical, emotional, or symbolic. Why is transformation such a recurring theme for you?

Metamorphosis is at the heart of my work because I deeply believe that identity is never fixed, but always evolving. My work with costumes and clothing has taught me that dressing is already an act of metamorphosis: when you put on a dress, you become someone else, or rather, you reveal a different aspect of yourself. In theater, this transformation is explicit—the actor becomes a character—but I believe it happens continuously, even in everyday life.

In my portraits, I try to capture precisely this: not a static identity, but a moment of transformation, a transition. I’m interested in instability, the tension between what one is and what one is becoming, between concealing and revealing. Even technically, watercolor is a technique of continuous metamorphosis: the water transforms the pigment, the paper absorbs and modifies, nothing is ever completely under control. There is always an element of unpredictable mutation.

Ultimately, painting metamorphosis is my way of saying that none of us is ever complete, never definitive. We are all works in progress – and it is precisely in this incompleteness that I find the most authentic beauty.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.