Christine Moog

Your education: MA in Medieval Italian Art History, MFA in Graphic Design, currently a PhD student researching female printers in London in the 17th century.

Describe your art in three words: visualising female absence.

Your discipline: book design, bookmaking.

Website

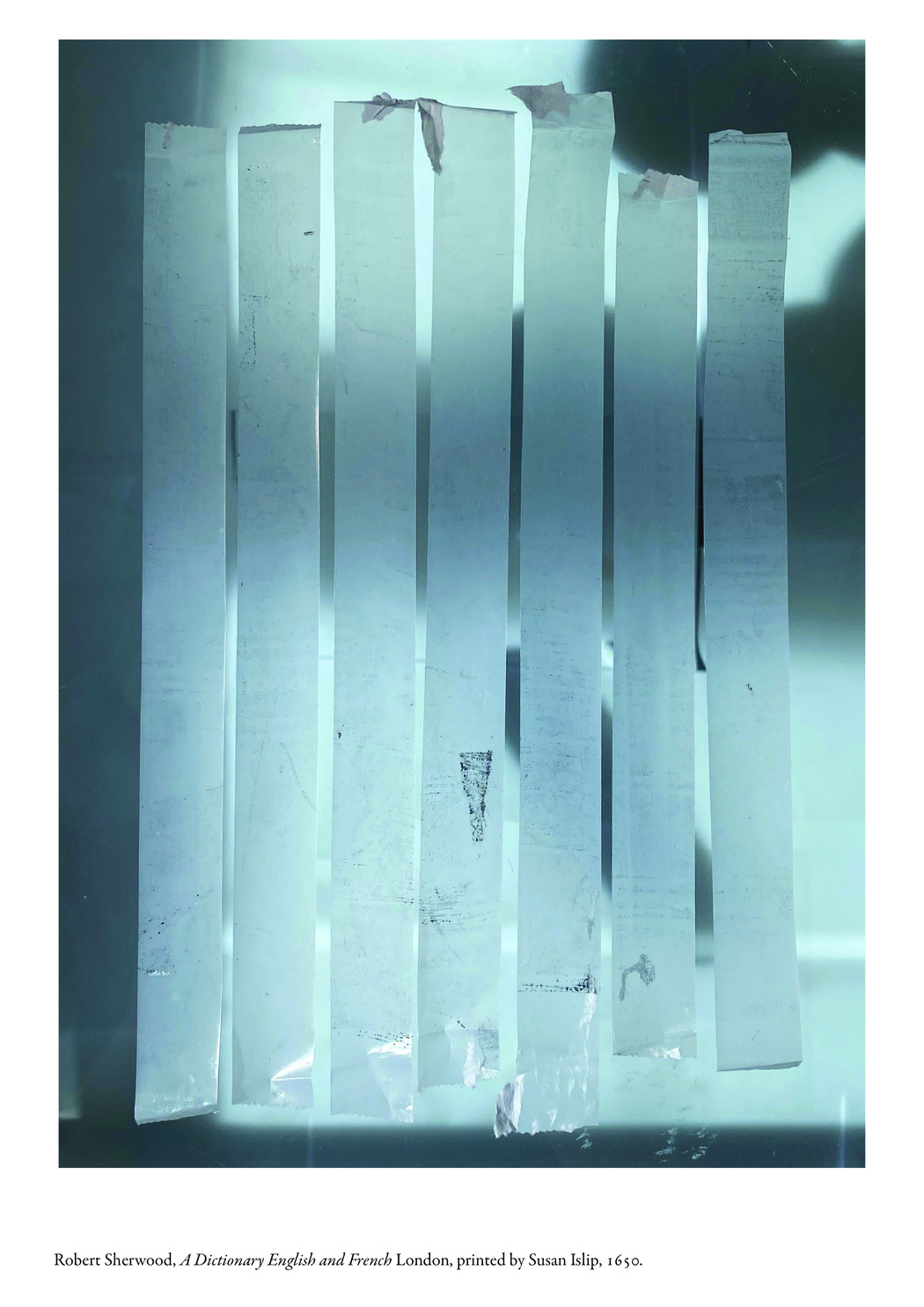

Christine Moog | Moog taped 1650

Christine Moog | Moog taped 1650

What initially drew you to the history of women in printing, and how did you discover Susan Islip?

My interest in female printers started years ago when I stumbled upon a fleeting reference to typefounder William Caslon’s wife. I stopped and reread the sentence as I thought I had misread it. A woman? Printing books? This was before the recent resurgence in the overlooked and undervalued. We know that women were printing books a mere twenty years after Gutenberg in the western Europe, yet their stories have been omitted from the historical narrative. As a female designer and design historian, the under researched area of women in the print industry is of particular interest. In terms of why Susan particularly, I actually had lists of other women from which I could have chosen. It was actually a process of elimination. I wanted to work on a London-based female printer who had printed more than a few books, but not hundreds, and I wanted to work on a printer in the 17th century. When I first started to research Susan only two or three of her books were known. I have since discovered that she actually printed ten books starting at the age of eighty. It is quite something. I think about all the other stories that still need to be told.

In Taped 1650, what role does materiality play in visualizing historical erasure and presence?

Materiality plays a large role. I am very interested in how practice can make visual these women that were erased from history books and our larger narrative. Only fragments of their lives exist in archives and we need innovative ways to recover and manifest their stories. My practice seeks to help combat historic inaccuracies—as absence is best expressed through presence.

Could you describe your process for transforming archival research into visual studio work?

Everything starts in the archive. Then, it is a process of research, reading, discussion, trial, error and reflection. Engaging with what is missing becomes an iterative process reimagining how omission can become visual.

What does it mean to “ungender” women’s presswork, and how does that reshape our understanding of authorship?

To ungender women’s work means to recognise their value and reclaim women’s involvement in knowledge production. It helps to provide a more complete, nuanced and truthful account of history.

How do you see the relationship between graphic design and historical reclamation?

Design can challenge dominant visual languages, filling gaps in the archive. I think an aesthetic response can probe our missing past and design can be an integral part of female recovery, shaping how information is presented and absorbed.

What challenges do you face in making invisible histories visible through visual media?

Archival research requires a lot of time, a lot of detective work and a lot of digging. The paucity of information can be challenging. In piecing lives together i want to be careful not to assume, as one has to straddle the line between fiction and innovation.

How do you balance the roles of researcher, historian, and artist in your practice?

They all inform one another. They are in constant dialogue with one another. I don’t think it’s about balance as much as constant interaction.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.