Hannah Lewis

Year of birth: 1959.

Where do you live: Balnarring, a small coastal village, south of the city of Melbourne in the state of Victoria Australia.

Your education: Bachelor of Arts, Diploma of Education.

Describe your art in three words: Australian flora.

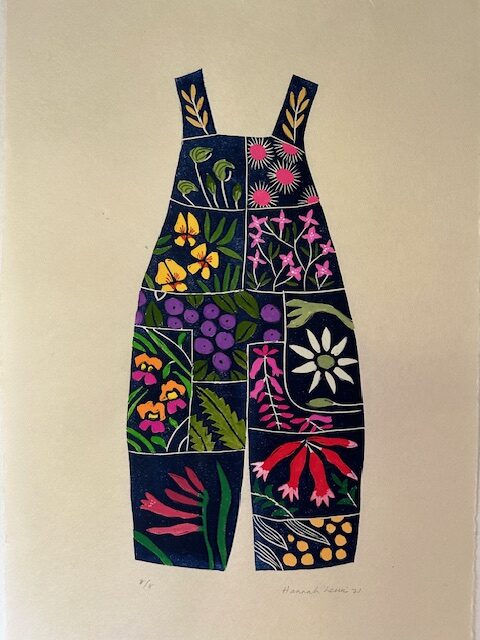

Your discipline: Hand coloured linocut prints.

Instagram

Can you tell us about the inspiration behind your use of clothing motifs in your prints? How do they relate to your connection with nature?

I started using the shape of a piece of clothing, such as a jumper or a dress, to ‘frame’ my linocut prints a few years ago. Just like a favorite woolen jumper feels familiar and keeps me warm or a cape enfolds me, walking in the bush I feel comforted and enveloped by the magnificence of the natural world. The clothing is a metaphor for nature’s embrace. I relish the details of the plants that I observe and photograph for their unique beauty. Just as nature holds me, an item of my favorite clothing provides a gentle space on a lino plate to carve the details of the bush I explore daily.

I have had a long-held interest in artisan-made textiles and clothing versus fast, synthetic fashion. I grew up with a mother, grandmother, and aunt who knitted beautiful pure wool Aran and cable jumpers that were warm, enduring in style, and lasted for a lifetime. I still wear the jumpers knitted by my aunt and have a viyella cotton/wool nightie, hand-embellished with embroidered sprigs of flowers and edged with delicate crocheted lace that was my great-grandmother’s.

My mother was also a ceramicist. She used a wooden kick wheel and gas-fired kiln in our garage to throw and fire bowls, plates, mugs, and hand-decorated planters, mixing her own glazes in buckets. She used innovative techniques such as wax resist and melted glass in her bowls in the 70s. I was influenced to have a deep appreciation of things that were made by hand. I love drinking my morning coffee from a favorite hand-thrown and glazed mug. I always think of the maker when I wear or use something that is handmade. I have a beautiful pair of fingerless gloves that were dyed with Cherry Ballart, a tree that grows locally and is of significance to First Nations people. The color is a deep mossy green that, to me, speaks of these beautiful trees with their pendulous, needle-shaped leaves and tiny edible berries.

I became more conscious of the impact of fast fashion and mass production on the environment and on the lives of the workers in factories who make our clothes when we visited my daughter in Ahmedabad in Gujarat, India, where she was studying textiles at The National Institute of Design.

Gujarat is a significant center for traditional textiles in India, and we were fortunate to visit communities and family businesses that had been producing textiles for generations. We visited traditional block-printing workshops where families dyed cloth using plants such as turmeric and saw piles of dried pomegranates and indigo vats used to produce complex, intricate, beautiful designs. I learned about the toxic pollution of rivers that had occurred in India as a result of mass production and the use of chemicals to replace natural dyes.

I love textiles and clothing woven from wool, nettle, linen, silk, and hemp, materials of the earth that are durable and authentic. They speak of culture, traditions, community, and connection. I have been embroidering some of my prints with silk and wool dyed with eucalyptus, madder, chamomile, neem, and calendula. All these plants are purported to have healing qualities. On my residency at Point Nepean, I visited the local museum and had access to their textile collection. I photographed a beautiful corset cover and made a chin colle print based on this item of clothing. I printed it on vintage Chinese tissue. I then embroidered the motifs within the lace. The process of sewing multiple layers of paper was quite meditative. My grandmother used to knit woolen covers for wooden coat hangers, and I incorporated a coat hanger in the print to hold up the corset cover. I embroidered it with woolen thread.

The ‘framing’ of flora in an item of clothing has become a metaphor of sorts for my values, my passion for the environment and involvement in activism to protect it, and my love and appreciation of textiles and functional objects made by artisans. I feel that we need to pare back our obsession with material things: transitory fashion, gadgets, the best and the latest products, and work towards restoring and protecting the land, our forests, bushland, and waterways. I used an image of a simple pinafore with a pocket for one print. I embellished the body of the pinafore in medicinal plants brought out to the ‘colony’ of Australia by white people, as a reminder of the familiar and their gardens in Britain. In the pocket, I placed potent medicinal plants used by First Nations people, the Bunerong and Boonwurrung people who lived on the Mornington Peninsula where I live. Colonizers carved up the land, fenced it, clear-felled it, and the hooves of their cattle destroyed important grasslands and nearly eradicated important food sources such as the yam daisy. I want to draw attention to the contradictions and what we have lost and still stand to lose from inappropriate development and land use.

You’ve worked as a printmaker for over 20 years alongside a career in education and environmental projects. How do these fields influence each other in your work?

I taught English and Humanities before stepping into a role that focused on the well-being of students. I started a long journey of working with staff and students to design innovative and entrepreneurial curricula that took young people out of the classroom to participate in art and horticulture-based projects in the school grounds. Our buildings were run down and degraded, but we had plenty of outdoor space and a blank canvas. We were lucky enough to be close to a Ramsar wetland in Westernport Bay, which was a tremendous resource. We worked together on a range of environmental initiatives and became the first state secondary school in Victoria to be a fully accredited sustainable school. I saw young people’s self-efficacy, self-worth, and self-esteem improve in leaps and bounds when they were given the chance to lead, design, innovate, and work as a team. They were involved in landscaping, growing food, creating sculpture, mosaicking, the regeneration of a bush block, and all sorts of community projects.

The natural environment had always been fundamentally important to me, and I trusted my instinct to take a risk and give the students the freedom and space to solve problems, design, and create on their own terms.

I have recently been taking linocut workshops for a local organization that provides carers’ retreats and respite short-term stays for families experiencing hardship. It has been joyous to see people flourish through a simple art-based activity when circumstances in their daily lives are often overwhelming and challenging. They each completed a small circular linocut print that they took home. I strung each print together in a ‘necklace’ of sorts as a metaphor for community strength.

While my work is generally solitary, it tells a story of place and the power of the natural world to ‘heal the soul.’ Whether it’s a jewel of a flower in my garden, the vibrant pink of seaweed on our local beach, the whisper of wind in the local bush, or the song of the spinebills in our garden, nature calls to me, and I love to share its details and beauty in my work.

Could you share more about the specific flora and landscapes that inspire your prints? Are there particular species or locations that hold special meaning for you?

The bushland and coastland on this side of Westernport Bay are my heart-place. I first started coming to Balnarring with my family 60 years ago. I moved to Balnarring permanently in 1984. We are lucky enough to have Coolart homestead and wetlands less than a kilometer away as the crow flies and within easy walking distance through coastal bushland at the end of our street. Balbirooroo Wetlands are a short walk to the north of us.

We walk around the wetlands and through the bush regularly. Coolart foreshore has a healthy colony of black wallabies, echidnas, antechinus, the odd sunbathing snake, and a plethora of birds. The sound of the frog chorus in the surrounding wetlands is like an evening chant in the wetter months. Merricks creek, which feeds into Western Port Bay, is at the end of our road and abounds with birdlife, egrets, wild ducks, and herons.

We have always walked the beaches close to where we live, but during COVID lockdown, I became far more acutely observant about the changes within that landscape depending on the weather, the season, the tide, and the time of day. We walked daily within the restrictions of a 5k radius with our kelpie, from Balnarring to Merricks and beyond. I was more cognizant of the plants marking the seasons with their flowers, fruit, and seedheads: a carpet of tiny white boobialla stars festooning the sandy paths to Merricks beach in late spring, glorious fragrant native clematis blanketing the cliff face in spring at Merricks, and wrapping the tree trunks along Merricks creek, native raspberries’ sweet summer fruit. Walking through casuarina groves, the tips of their long dangly pin leaves shimmering gold in summer and the breeze rustling through them has a whispering sound that is soothing. Erect Golden banksia cones grow in the sand, survivors of the high tides on Merricks beach.

Tones and nuances of seasonal skies and waters are everchanging; blanketing mists and frigid air in winter, rolling back to blue skies, gentle blush of pink sunset in the colder months compared to the fiery, gaudy summer sunsets. Silver water at dusk glistens with a metallic sheen. The full moon reflects on inky black depths on moonlit walks.

My garden has been sculpted from scratch over 40 years. It has evolved as my knowledge and love of Australian plants and understanding of the importance of local providence plants have grown and matured. It is abundant with fruit trees, vegetables, herbs, and Australian plants, and the birds that enjoy this habitat: Eastern rosellas, cockatoos, wattle birds, scrub wrens, and Eastern Spinebills, to name a few. We even had a family of 5 blue-tongued lizards at one stage. I love the local kangaroo, wallaby, and poa grasses that now self-seed everywhere, the meter-tall rogue asparagus that appears every year under my rosemary bush, but most of all the banksia that stands sentinel beside our driveway with its huge golden wiry flowers that stop people passing by in their tracks.

I make pesto from nasturtium leaves, summer basil, wild rocket, and coriander that have self-seeded. We drink tea from the garden: lemon verbena, Tulsi (holy basil), strawberry gum, and lemon myrtle. The garden sustains and feeds our family, provides material and inspiration for my prints, but first and foremost, it restores and grounds me. The simple acts of having my hands in the earth, digging, planting, weeding, and harvesting, cutting flowers for the house or specimens for my prints, keep me hopeful and purposeful. I have the joy of sharing it with friends, my family, neighbors, and the community.

During your residencies, especially the floating residency on Lake Tyers, how did the environment impact your creative process?

Bung Yarnda (Lake Tyers) had a significant impact on my practice. It was an astounding place. To be living and working on a floating studio–residency for four weeks was such a privilege. To kayak and live on an extraordinary body of water (It is a designated internationally recognized Ramsar wetland) and listen to birds alighting from the water, feeding, and flying overhead, to see the changes of light and movement on the water, the morning mists and evening sunsets of a dramatic scale was transportive. I have always loved writing, but I realized that the narrative behind my work is an important part of the whole picture. At first impression, you could be forgiven for thinking ‘It’s ‘just a pretty dress,’ but there is a backstory to each work that tells a story of place, habitat, and ecosystems and of the preciousness of our indigenous flora, so much of which has been destroyed and degraded through farming, development, and the practices and ignorance of the colonizers’ mindset. The tragic thing is that despite what we now know about the impact colonization has had, the pollution, destruction, clear-felling of land rich in biodiversity, and the mining of places that are culturally significant to First Nations People, it continues today.

My response to this residency was to record the details of walks that I did, looking at specific plant groups. For example, the vegetation along the shoreline that I kayaked to every day was a pristine example of intact shoreline vegetation that has evolved to cope with regular inundation when the lake fills in the wetter months. One of my prints features the plants that grow along the shoreline: sea parsley, knobby club rush, common reeds, warrigal greens, samphire, yellow button flower, and rounded noon flower.

The chance to really immerse myself in the landscape and experience real solitude over a four-week period on the lake enabled me to really feel a sense of place. I felt as if my senses became attuned to the nuances and moods of the water and landscape.

Your work seems to carry a strong narrative about the healing power of nature. How do you hope your audience feels when they engage with your prints?

I hope people are reminded that, despite the ever-present horrors unfolding in our world and the damage to precious environments, there is so much beauty in the natural world. It can be found in a flower growing through a crack in concrete rubble, the way gold light filters through tree branches at the end of the day, or the sound of water trickling after rain. My practice focuses on the minutiae in the bushland around me and on walks further afield in less familiar places, rather than the grand sweep of the landscape. It is so much about walking with intention to absorb the sounds, scents, and details of the land I walk on, to feel a sense of place. We can so easily walk without seeing.

When I worked in education, I saw young people that hated school, were disengaged, or faced daily trauma in their lives transform when we took them outside to work in green spaces and in bushland. It was as if they could breathe again. Having access to nature and green spaces around you is so important. I hope people can feel a fragment of the delight and joy that I feel when I find these precious jewels peeping from the bush.

Can you share any details about your upcoming solo show in November? What themes or subjects will be highlighted?

The exhibition will feature three distinct bodies of work: early work from COVID Lockdown in 2020 through to 2021 when my daily walks became so important, and I started to notice the changes in the landscape more acutely. The second body of work will be from my residency at Police Point, adjacent to Point Nepean National Park, on the furthermost part of the Mornington Peninsula where I live. It features the plants and animals I saw on my daily walks and references to historical detail and narratives. The final body of work will be from my four weeks on a floating studio/residency on the Ramsar wetland Bung Yarnda (named Lake Tyers by colonizers). Each body of work evokes a sense of place. People who know those locations and walks will recognize the flora. I chose the title “Flora” for the exhibition because it is both a woman’s name and the Latin word for flower. Flora was the fertility goddess of flowers and springtime in ancient Rome. Walking in the bush and working in my garden gives me a sense of hope when the world is unraveling, and we are facing an escalating climate crisis. I hope people can walk away from the exhibition with a sense of how precious plants are and how we need to value and care for our environment no matter where we live.

What advice would you give to emerging artists who are also passionate about environmental issues?

Build connections and immerse yourself in finding out about artists whose practice speaks of the environment. Look broadly and keenly at artists from all mediums: writers, poets, musicians, performers, and jewelers. Keep journals, something I have only seen the value of more recently, as narrative has become an important part of my practice and telling my story of place. When you are overwhelmed by what is happening in the world, read for inspiration, get involved in community arts and campaigns. My involvement in three local environmental campaigns helped me to find ‘my people’ and a sense of community, connection, and belonging. This is important as artists often work in isolation, alone with their thoughts. Channel your anger and despair into your art. My daughter, who studied Fine Art, gave me the best bit of advice. I rang her after I had torn up a botched failure of a print. I had spent the day cutting the plate and when I printed it, I hated it. I felt like giving up, that I was a poor excuse for an artist. She said words to the effect of ‘You only create for yourself. Don’t try and make something that will please others.’

Leave a Reply