Wallace Woo

Your technique, “Acrylic with Ink Spirit,” balances fluid spontaneity with precise control. How did this approach emerge from your background in fashion makeup artistry?

I am deeply grateful that in the first half of my life, I had the opportunity to work as a makeup artist in the dazzling world of fashion. Everything this profession bestowed upon me—from a heightened sensitivity to color, light, and form, to the ability to shape texture and capture transient moments—has profoundly shaped who I am today. Yet, I have always held a clear wish in my heart: I hope people will eventually call me an Artist, not merely a Makeup Artist.

This shift in identity stems from a deeper level of self-reflection. My rich experiences in the fashion industry broadened my horizons but also amplified my desires, ultimately leading me back to the most fundamental level: to perceive my true self and explore the more essential values of life. Painting became the medium for this journey.

I discovered an innate affinity within myself for the ethereal, formless quality of Eastern ink wash painting. It embodies a philosophy of “gaining through letting go”—much like sculpting jade, where removing the excess reveals the radiant Buddha within. However, I equally cannot abandon the training in form, structure, and active expression I received from Western art education since childhood. My unique cultural identity compels me to ask: How can I find my own balance between Western “creation” and Eastern “relinquishment”?

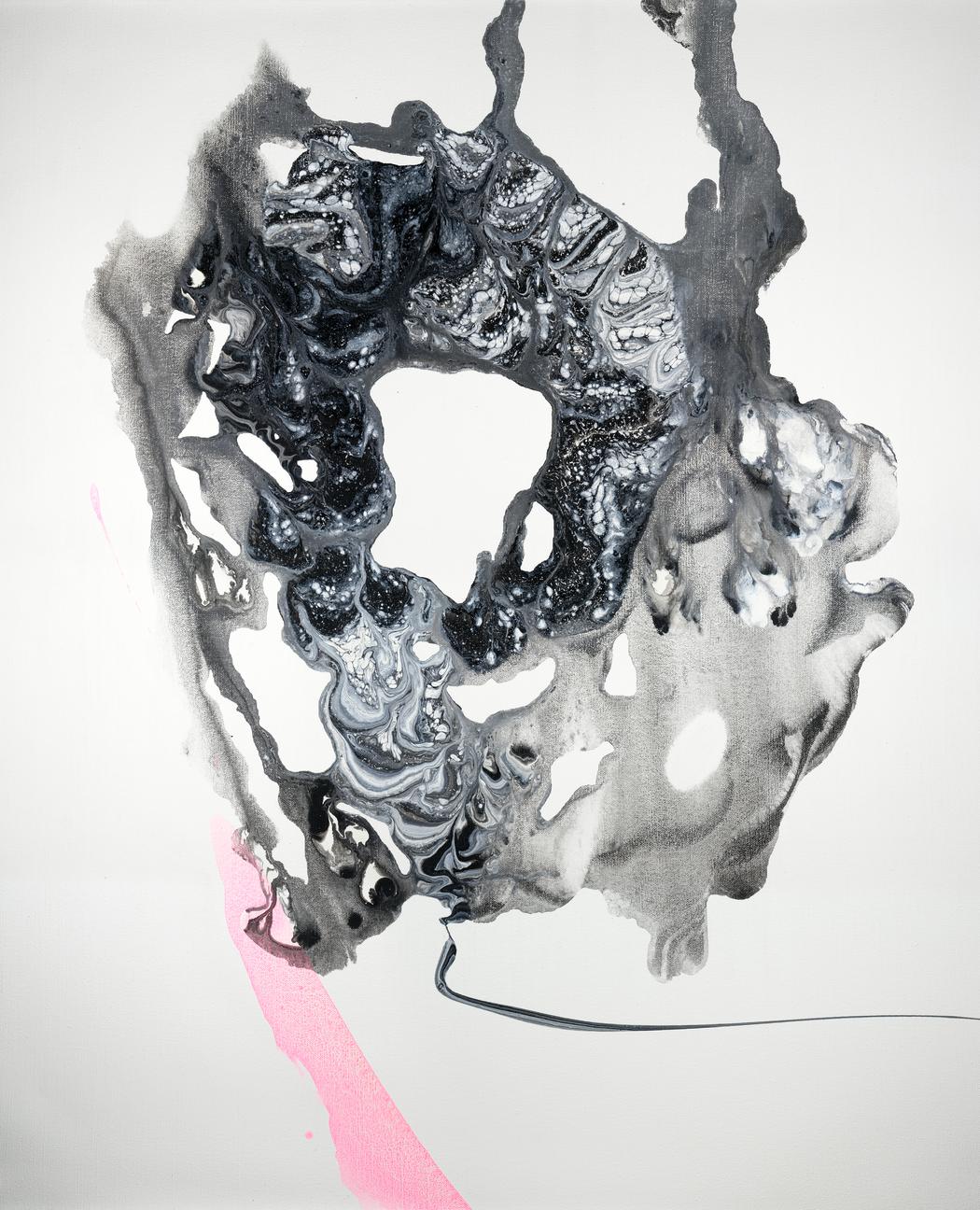

Thus, my technique, “Acrylic with the Spirit of Ink,” became a bold experiment. I thin fast-drying, dense acrylic to an ink-like transparency, pour it onto the canvas, and within the brief window of its free flow and manifestation, I engage in precise intervention and choice. This process itself is my core creative philosophy: learning to let go within creation, embracing chance within control.

This experiment has no final “perfect” answer; it is an ongoing process. For me, the value of art lies precisely in this: continually perceiving, creating, and letting go. Within this cycle, I approach that state of “eternal becoming.” And what remains on the canvas is the most honest evidence of this journey.

Your works often feel like they are forming and dissolving simultaneously. How do you decide when a piece is complete, especially in such fluid, evolving processes?

I am deeply immersed in a state of heightened concentration throughout the painting process, constantly attuned to the shifting reality before me—every fleeting state of the pattern as it moves across the canvas. The most fascinating aspect of fluid painting is that even the subtlest flow carries an indescribable sense of motion in the moment, both tangible and elusive, present yet intangible. My creative process is one of using slowness to master speed, while simultaneously racing against the drying time of the paint to make rapid, precise judgments about each emerging form. It is a contradiction, but then—isn’t life itself just like that?

Through Zen practice, I have learned to accept all the changes life brings. Pain passes, sorrow passes—there is no need to cling to what is unnecessary. I sense whether the emerging patterns and my inner awareness connect, and naturally, a strong impulse arises within me to extend the uniqueness of those forms. As for deciding when a work is complete—as an artist looking back on past creations, I always feel something could have been done a little better. So, in truth, there is no absolute “completion.” Instead, I would say a work feels comfortable more than it feels “finished.”

It is like the feeling of love at first sight. When you encounter a stranger, do you step forward to greet them, or let them pass, preserving a space for imagination? That tension between reaching out and holding back—that precious, trembling in-between—is where the essence lies. My painting finds its pause not when everything is resolved, but when that moment of poised uncertainty feels alive, breathing on the canvas… and quietly settles into my soul.

Vipassana emphasizes awareness of impermanence. How does this spiritual practice shape your relationship with each artwork as it emerges and transforms?

The awareness of “impermanence” emphasized in Vipassana meditation is not merely a philosophical concept to me, but the most fundamental mind-body state I enter when creating each painting. It has completely reshaped my relationship with the work: I am no longer a “creator” building from nothing, but more like a practitioner learning to “witness” and “respond” within the flow of change.

The flowing, blending, diffusing, and settling of colors on the canvas are themselves the purest visual manifestations of impermanence. Every second, forms are born while simultaneously fading away. What Vipassana first taught me is “simply knowing”—knowing the paint is flowing, knowing a surprising texture is forming, and also knowing a beautiful shape I had anticipated is dissolving. In the past, that “dissolution” would instantly trigger inner anxiety and grasping. I would rush to intervene, trying to “save” or “fix” the moment I favored. Yet, often, such intervention born of fear is like trying to hold running water with bare hands—not only futile, but also disturbing the poetic path the flow might have taken, one I had never imagined.

Vipassana gives me a space to breathe. When the thought of “wanting to pull it back” arises, I can recognize it and choose to return to an open awareness, trusting the material’s own wisdom. This trust is not passive abandonment, but a subtle, timely participation within intensely focused contemplation. Like a surfer moving with the wave, I do not control the paint. Only after fully accepting “impermanence”—accepting coverage, accepting unexpected color mixtures—am I released from the tension of “fearing loss.” My mind becomes calm and clear, enabling me to “hear” what the canvas truly needs: perhaps a stroke to contain, perhaps an area of blank space.

My relationship with the work is an ongoing, silent dialogue. The work changes, and my awareness flows along with it. I do not ask, “What do I want to make it into?” but rather, “What is it becoming? How can I participate in the least destructive way?” Completion is no longer a static endpoint, but a fulfilling pause naturally reached in the dialogue. When I feel all the energy, all the movement, all that has “happened” and “not yet happened” on the canvas reach a dynamic, breath-like balance, I know it is time to let go.

Those works “completed in one sitting” are precisely the traces of this practice. They honestly record the quality of my awareness, my courage, and my limits in that moment. They remind me that the power of art lies not in eternal solidity, but in its candid revelation of the entire process of becoming, abiding, and dissolving—just like life itself. Each painting is a collaboration with impermanence, and the peace and freedom the heart finds after letting go of attachment.

Black, white, and muted tones dominate your palette, with occasional subtle colors. How do you approach color as a symbolic or emotional element rather than a purely aesthetic choice?

In my exploration of color, I have undergone a journey from outward expression to inward reflection. Initially, I did experiment with a riot of colors in my work, as if pouring all the brilliance I witnessed in the fashion world onto the canvas. However, those works were eventually destroyed by my own hand—they held no “feeling” for me, merely a lively veil that could not touch the soul. I gradually realized that this might be a profound misdirection brought by my career as a makeup artist: I once thought I lived in a world full of color, only to later awaken to the fact that many of those colors were “costumes” applied for others—external, temporary, and serving the visual. They were not the true reflection of my inner landscape.

Thus, I conducted a resolute experiment: I removed all colors from my palette, leaving only black and white. This was not a negation, but a purification. When the world shed all its colorful garments, an indescribable “sense of substance” rose from within. Black and white became the purest light and shadow, the most essential contrast. They constructed the depth of space and the weight of time, allowing me to focus on the growth of forms, the flow of energy, and the internal structure. This is the visual truth I have always sought—not the appearance of the world, but the skeleton and breath behind it.

Yet, this does not mean I reject color. When cool tones like deep blue or lavender occasionally emerge, I do feel a distinct “resonance.” This is not a random aesthetic choice but rather as if these hues themselves carry a certain emotional frequency or spiritual temperature. This allows me to perceive an intuition connected to the chakra system—deep blue seems to link to the throat chakra’s calm expression and the intuitive eye, while lavender touches the awareness of the crown chakra and the inner vision of the third eye. To me, they are manifestations of specific internal states, the natural emergence of a “texture of light” when energy reaches a certain level. Therefore, in my paintings, color is never decoration but the direct topography of emotion and spirit; the occasional infusion of a cool hue is a subtle glow of spirit within the silent space-time constructed by black and white.

Your process seems deeply physical despite its meditative foundation. What role does the body play—movement, gesture, breath—in shaping each composition?

In the creative process, my body is not merely a tool executing commands from the mind; it is a “guiding entity” unified with spirit and breath. While many perceive meditation as static seated practice, for me, when I am fully immersed in a state of flow, the entire act of creation becomes a dynamic Zen training ground. Within this dedicated space, every movement of the body, every breath, is no longer just a physical act but an internal force that directly participates in shaping the painting.

When I pour paint or tilt the canvas, my movements are not arbitrary but a form of conscious “bodily writing.” The arc of my arm’s sweep, the subtle turn of my wrist, even the shift of my body’s center of gravity—all leave irreplicable traces in the flowing medium. These traces are the most honest dialogue between body and material. Breath, meanwhile, acts as the metronome of this conversation. In moments of held breath and focused stillness, I intervene and guide; in long, deliberate exhalations, I observe and wait. The rhythm of my breath naturally modulates the force and timing of my actions, preventing the process from becoming rushed and chaotic or hesitant and stagnant.

Thus, before the canvas, my body is like a dancer moving with water. It does not fight the fluid but perceives its gravity, tension, and speed, responding and collaborating with corresponding gestures. In the end, what solidifies on the surface is not only the trace of color but also the “testimony of presence” forged in that moment by the synergy of bodily momentum, respiratory rhythm, and fully concentrated energy. Creation, for me, is precisely this dynamic meditation—a resonant state where body, mind, and material become one.

Many viewers describe your works as meditative portals. What emotional or contemplative state do you hope they enter when encountering one of your paintings?

When I create these works, the anticipation I hold in my heart is not for viewers to “take away” any specific message or story. Quite the opposite—I hope they can let go.

Let go of the daily clutter, let go of the mind that rushes to interpret meaning, and even let go of the unconscious tension that comes with “viewing art.” When you stand before the painting, I hope the silence woven from layers and flow can serve as a buffer, gently separating you from the noise of the outside world. It is like entering a cave—the initial darkness and silence may feel unsettling, but as your eyes and mind gradually adjust, you begin to perceive the texture of the stone walls, the sound of dripping water, and the vast, gentle flow of time itself.

What I wish to guide viewers into is a state of “aimless focus.” The gaze can wander along the edges of color layers, sensing the weight and delicacy of pigment sedimentation; thoughts may settle in a corner where ink softly blooms, much like the mind finding a blank space to rest. Within this focus, we might touch upon a more fundamental experience: a simple awareness of our own existence, of our breath, of the present moment.

These paintings depict geological time, the slow pace of growth. Thus, I hope they can create a psychological space of deceleration for the viewer, allowing one, in a moment of pause, to untangle from the chase of the social clock and experience another expansive quality of “time”—it is not meant to be filled, but to be inhabited.

Ultimately, what I hope for is that the canvas becomes a mirror reflecting the inner self, not a window defining a view. The traces I depict are merely an invitation. What the viewer truly encounters depends entirely on themselves—it is the stillness within them, the depths, or the light they are prepared to see at that moment. Thus, before the same painting, one person may encounter a pond of serene stillness, another may see their own unspoken thoughts reflected, while yet another might, within those shades of grey, recognize for the first time a faint yet certain light that belongs to them. This is the meaning of art as a “mirror”: it does not provide answers. Instead, with its silent depth, it invites every person who pauses before it to engage in an honest, gentle, and open dialogue with themselves.

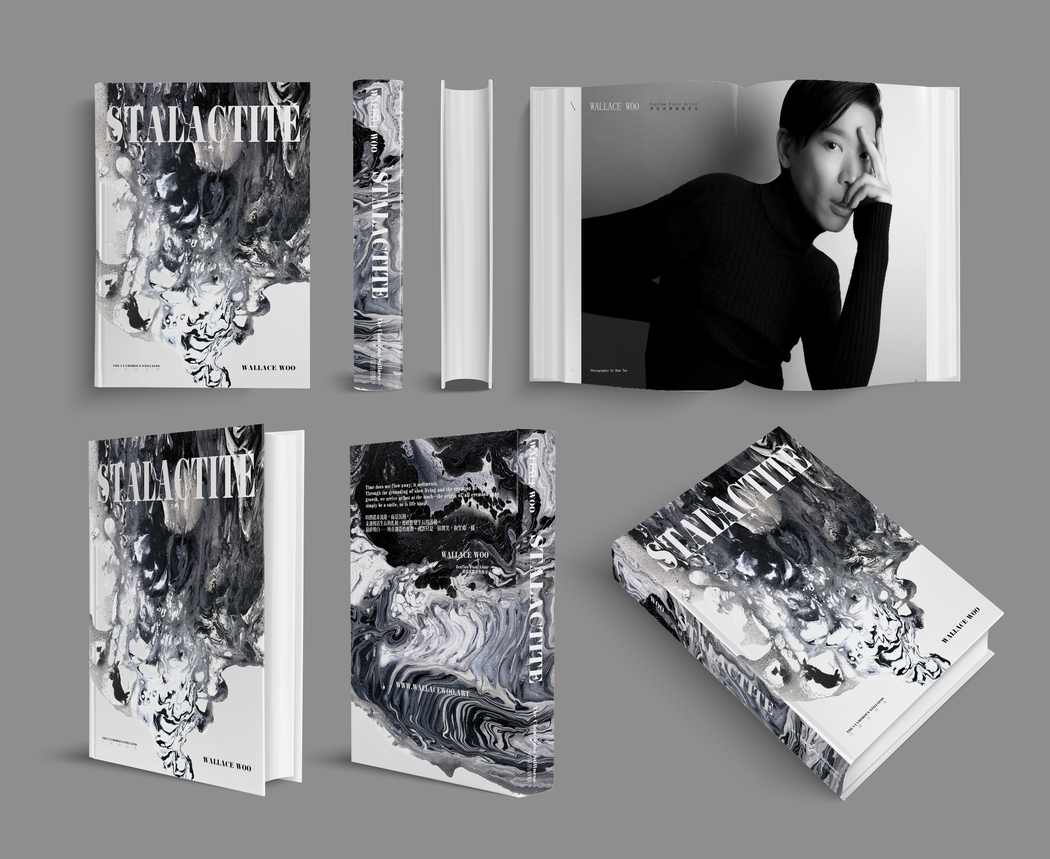

Creating a series of 99 works is an immense artistic journey. What inner transformations or realizations accompanied you through the creation of “Stalactite”?

Through a long and uninterrupted creative process, to claim that thoughts of giving up never surfaced would indeed be untrue. I am honest that on certain days, I would grow weary of the sight before me, even deeply doubting my own worth—having created so much, the works stacked quietly at home were like silent words only I could hear; there was no audience, no echo. When would those destined to resonate with them ever appear? This silent inquiry would occasionally lead me to the edge of abandonment.

For me, painting might have begun merely as a way to pass time and channel emotions. But gradually, a longing also arose within my heart—a longing to be seen by the world. Only by being seen could these quiet cultivations of mindful awareness possibly flow outward and touch another heart. Yes, I am so conflicted: I am both immersed in the purity of solitary creation and yearn for resonance; I find myself in loneliness, yet feel unsettled by it.

Yet, as if drawn into a ritual of obsession, within those repetitive motions—painful yet quiet—whether in the daily act of painting or the subsequent documentation of the works, a truth gradually became clear to me: creation itself is the most fundamental way I engage with the world. When I asked myself, “If I don’t create, what else can I do?” the answer was often a void of silence. Since there seemed no other choice, I might as well move forward, transforming this time into a meaningful accumulation, even if the world had yet to notice. I began to understand that the seemingly lonely process had long been rewarding me: it was an irreplaceable focus, a depth of being with myself, and an internal order formed within silence.

The creation of the Stalactite series was precisely a prolonged process of “inward rooting.” The accumulation of 99 works allowed me to personally experience what “the sedimentation of time” means—occurring not only on the canvas but within my very life. This process also completely redefined my understanding of “completion.” I no longer saw each painting as an object to be “perfectly finished,” but rather as a node within the entire growth process. The 99 works are like 99 slices of time, collectively documenting a history of conscious sedimentation. What matters is no longer the impact of a single image, but the intangible, complete trajectory of growth formed by all the works, together with the silences, hesitations, and perseverance in between.

I came to realize that an artist’s value is not defined solely by external attention. Just as a stalactite in a dark cave silently forms its own shape and luster through the accumulation of each drop of water, an artist’s creation is also a form of self-completion that requires no external permission.

This series is a metaphor and a tribute to all creators who work diligently in silence: we need not rush to be seen, because true light comes from the act of sustained growth itself. In the end, what I completed was not merely a series of works, but an inner conviction—the meaning of art lies first in whether we are willing, through long and quiet stretches of time, to remain faithful to that drop of water within the heart, letting it fall, sediment, and ultimately crystallize.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.