Mike Efford

Year of birth: 1953.

Where do you live: The town of Cobourg, just east of Toronto, Canada.

Your education: Fine Art diploma from Humber College/Guelph University (1977) and Continuing Education art and design studies from 1980 to 2014 at Ontario College of Art & Design, Centennial College, Toronto Metropolitan University, and more recently Toronto School of Art.

Describe your art in three words: Three dimensional landscape.

Your discipline: Mixed media sculpture.

Website | Instagram

Mike Efford | Flowerpot Island

Mike Efford | Flowerpot Island

Your career spans graphic design, coin design, and 3D animation—how did these disciplines influence your approach to sculptural landscape art?

My first art job was designing and sculpting coins. Lasted for 4 years, in a Canadian company called Interbranch International Mint. A private mint! Go figure. There were maybe 3 or 4 in all of North America back then. Us, Franklin Mint and Sherritt Mint out in Alberta. It was at the height of the gold boom in the late 70’s, early 80’s. Which is back! Anyway, beyond designing in the round, the skill set required was bas relief sculpture. Now, relief sculpture is unique and full of paradox. Far less depth than in-the-round figure sculpture, technically, yet capable of pictorially illustrating vastly more depth, an entire landscape or scene! Check out Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise doors in Florence, (which I saw many years ago) you’ll see what I mean. So that approach to 3 dimensional art never really left me. Wall sculpture is a cousin to relief sculpture. Essentially frontally viewed but capable of suggesting nearly infinite depth, especially as a work of 3D collage. And 3D animation uses wireframe models, built in multiple layers, which are related in many ways to the multi part structures I create today.

What initially drew you to explore landscape through a non-traditional lens?

A lot of the graphic design and 3D motion graphics work I did involved multiple viewpoints and montage, and I found I could create with that mindset using real world materials to make sculpture. I think there are so many ways to interpret landscape beyond the usual stuff you see out there, no matter how well executed. I became aware of the later sculptural work of Frank Stella, just to give an example, that showed what you could do if you just took that leap! So I did.

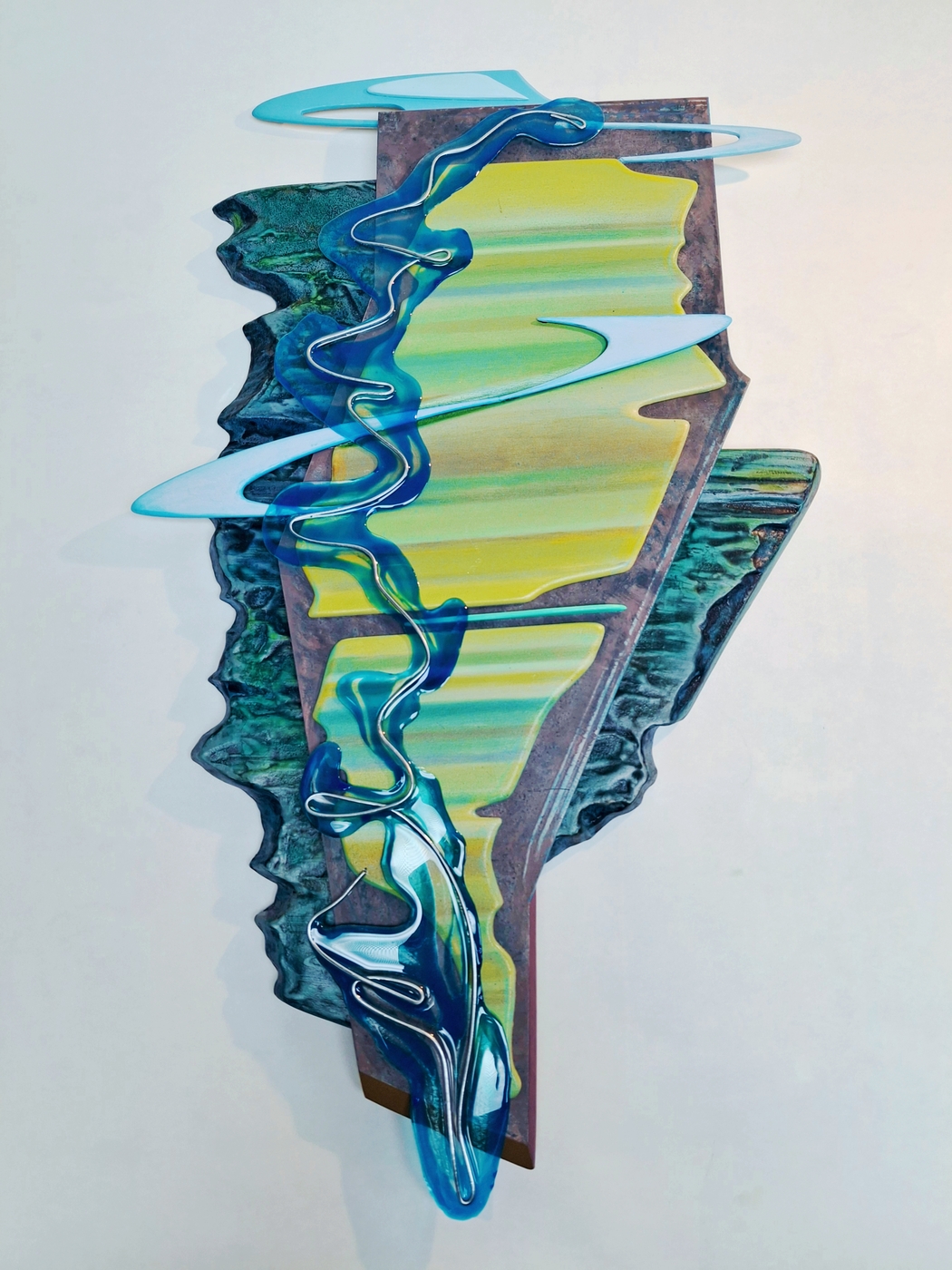

Mike Efford | Tides

Mike Efford | Tides

Many of your works integrate forms that resemble scientific diagrams or maps—how do you see the relationship between nature and data in your practice?

Nature is the source, data is humankind. To me, science, technology and even agriculture are mark-making. All of them involve some form of drawing, within and upon nature. A jet’s wing displaces air to create lift through vectors, giving flight to the aircraft, which then draws a line through the sky. A tractor draws parallel lines on land. Drawings! The aerial view frees up vision, I find. So maps, seen from above, are humankind’s grand conceptual drawings, overlaid upon the geography of the earth. It’s intrinsically beautiful. And limitless. I find mining geology visualizations quite fascinating, for example. There’s an unconventional viewpoint for you, right? A view deep inside the earth, not necessarily of the surface appearance at all. Some of the technologies that locate veins of ore deep in the ground, are visualized on computers with transparent colour shapes, lines, textures and graphic symbology that react to unseen bodies of the same metals used in fine art sculpture. Again, mankind’s drawing, and a unique kind of technological landscape art. All of it inspiration for sculpture, to me.

Could you describe your process of translating digital landscapes into physical mixed-media sculptures?

Sure, so these days actually I generally start with a line drawing, the fastest route from the subconscious to a concept. However I did for several years take digital photography and process it with filters and such, to create my own language of texture, which by the way I often carry forward into my present work. And before that I used the same digital tools I used for 3D animation models, to improvise land forms, then apply digital processing, to create landscape prints. But these days I sketch, gesturally and pretty loosely, I guess, to kickstart an idea. Then I look at the lines, and in my head I conjure up form from them, very similar to how I worked on screen doing digital landscapes. But instead of different layers in a CAD file, I see different areas and materials, each working together to compose a landscape. I tend to evolve, but not necessarily discard.

Mike Efford | Terrain Fragmentology

Mike Efford | Terrain Fragmentology

Your pieces often incorporate flowing lines that resemble rivers, veins, or energy—what do these lines represent to you?

Line to me is the most indivisible, irreductible element in all of art, and also the most direct expression of form. Put it to the test! You have one second to express a sphere. Go! What did you do? You drew a circle. You didn’t shade anything, right? Line is this universal language. So versatile! And beyond a shorthand for form, it perpetually astonishes me how even a compact, casual scribble can exude massive energy. Like the kind of energy surging through a river, or the path of a bird wheeling and swooping through air. Line is magic. Line to me is a revealer of energy. Even when it’s just used to outline something. One thing I have done all my life is randomly scribble on paper, it’s a nervous habit, and an expression of raw energy I guess. But that turbulent, flowing line brings landscape to life. And in ways you might not expect.

How does your background in 3D animation affect your sense of space and layering in sculpture?

I was a computer animator for 26 years. I focused initially on motion graphics, much of it 3D flying logos and 3 dimensional graphics, and for the last 15 of those years worked with technical subjects, marketing new technologies, many of them yet to be even prototyped, let alone manufactured. Pure concept stuff, many times to pitch investors. Especially with the technical stuff, 3D models actually consist of a layered set of parts. It’s standard with pretty much all file formats. You open a 3D object file and you can click through sometimes dozens of separate elements or sub-components of the model. And working that way truly became part of my spatial DNA! Very different process from a sculptor who works in granite, for example, taking one large block and chiseling away at that monolith till the subject emerges, all in one piece. So this layered digital approach quite naturally led to a similar approach with real materials, and I began to make multi-part 3D collages of landscape. I’m essentially the kind of sculptor who likes to put things together. Even 2 dimensional collage is an assembly, and my process certainly is an additive one. Regarding my sense of space, many 3D animation projects I worked on involved building a full, realistic landscape in order to showcase some piece of tech moving or flying through it. So you kind of get a really expansive sense of sculptural space doing that. And since my work is essentially collage, I typically combine elements that reference a diverse set of viewpoints, all into one sculpture.

Mike Efford | Terrain Aeriality #2

Mike Efford | Terrain Aeriality #2

What role does materiality play in your practice? Why basswood, resin, stainless steel wire?

I’d say I’m actually not the kind of sculptor who really showcases the intrinsic qualities of his materials, the way David Smith brought your attention to wire-polished, welded steel, or the way Noguchi made the material granite take on a life of it’s own, regardless of the shapes he created with it. I’m more agnostic, and also part of me is still a painter. Colour and texture matter enormously to me, and my process allows me to turn on a dime, to change my mind on the fly as I play creatively with the finishes of of the various components I’m working on. Something you can’t really do if you’re locked in to the qualities of one material. Halfway through carving a block of granite you can’t just say, naw, colour here is off, needs to be more reddish. I keep colour options and even material choices open as long as possible, and try and conduct them like musical instruments in an orchestra. And the instruments themselves? Well, basswood has almost no grain, it’s easy to carve, and can be super smooth. Resin is my newest playgraound, massively versatile, especially for transparent bits of course. And stainless steel wire lets me express that energy of line I mentioned before. All told, there are entire worlds to be explored when these things are combined into landscape sculpture.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.